By Chrisfremantle

The formal beauty of John Newlings’s work belies his self-questioning and interrogation of our relationship with the more-than-human world.

Reviewed by Anne Douglas and Mark Hope, unfortunately Newling’s Dear Nature exhibition at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham is a victim of the current lockdown. This in-depth review is for the time being your guided tour. Anne and Mark are Board Members of The Barn, a multi-arts organisation in Aberdeenshire that focuses on the relationship between art and ecology. John Newling was artist in residence at The Barn (2015-17) and continues to actively engage with and support the development of the organisation.

In the corner of the gallery, the last work of John Newling’s exhibition is entitled ‘Reconciliation Steps’ (2019). It consists of a mirror and a rubber stamp on a small shelf. Looking into the mirror, a text reads “We have signed our names in your soil. So sorryâ€. This work evokes John’s response to the reality of the Anthropocene. As stated in the exhibition text, John is determined to understand “what it is to know that we have profoundly affected our environment… you can trace our evolution to a point where we have subdued nature, but to our own cost because we will make ourselves extinct.†This is the sharp, critical end of a stunningly beautiful, formally aesthetic body of work, which moves between nature and culture, materiality and ideas, interwoven with different notions of time.

What is it to know that we have profoundly affected our environment?

The Dear Nature exhibition is situated in three large rooms that open into each other on the second top floor of the Ikon Gallery. As the title implies the work addresses nature throughout, at times with a deep sense of awe, at others profound curiosity and at others of irony, “Can we ever truly be together (with nature)?†John asks (Newling 2018).

“It is learning that deepens our love.†(Newling 2018 ‘3rd February, 2018’)

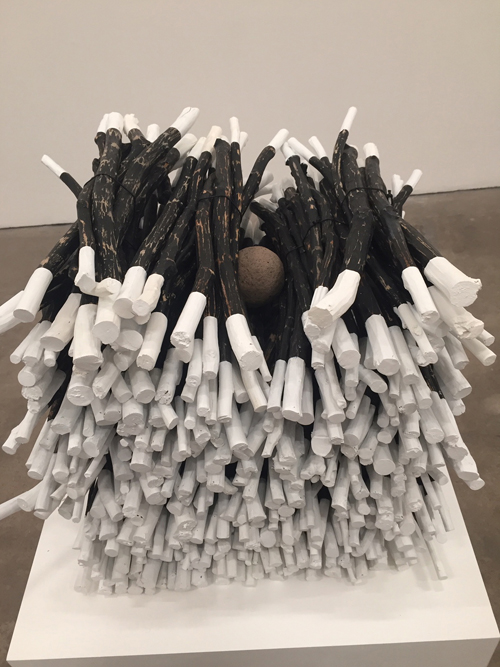

In the first room ‘365 days and 50 million year old leaves’ (2019) consists of a row of carefully constructed stacks of sticks that are as identical in size and shape to the extent that the material allows. John picked up a stick every day for a year, cut each one to the same length and blackened each of them with charcoal, then painted each end white.

In this way John joins the cycle of growth and decay in nature, interrupting it by transforming abandoned branches into ‘stick wands’, then into formal sculpture. The similarity yet difference between one stack and another exposes the singular, wilful character of each stick. We come to realise that they are each unique forms of energy that are particular to the time and place in which they have grown, then fallen. It is as if by interrupting the trajectory that nature has set from growth to decay, by collecting and transforming what nature has given, a new element is introduced. The three stacks feature other objects including soil balls, feather quills and an ink well that extend the play and tension between nature and culture. The reference to magic in this relationship is strongly present.

John’s artistic process involves a deep paradox. His way of making art is rigorous, painstaking, structured and controlled and yet the outcome also feels improvisatory, as if somewhere along the way chance and serendipity had played their part.

John Cage, the experimental composer and visual artist, once criticised improvisation: “Most people who improvise slip back into their likes and dislikes and their memory, and don’t arrive at any revelation that they’re aware of†(Fiesst, 2009). Cage wanted to free sound from personal taste, to let sounds be themselves. It is this quality of letting things ‘be themselves’ that John evokes again and again in this exhibition; the sense that the work we are looking at ‘happened’ or ‘occurred’ in ways that were unpredictable and unforeseeable, even to John himself. He attends to the work in progress, continually responding to its emergent life.

In the second room of the three rooms we encounter ‘From my garden’ (2018), a large work in copper leaf and paint which creates a different record of John’s practice of collecting. This time it is a leaf from every tree within his garden. The leaves are formally organised in a grid and once again it is John’s particular approach to form building that frees the singular shapes of each species and reveals the immense variability across species. This play between determinacy and indeterminacy, between degrees of control and openness to serendipity and chance, is a distinct quality of both Newling and Cage’s work. It is a particular quality of freedom that is does not stand in opposition to constraint. Both artists evoke the way energy moves through material in nature, the blood through arteries, the wind through water, movement that is made possible by being contained, constrained but, free not just from personal taste, but also individual, human control.

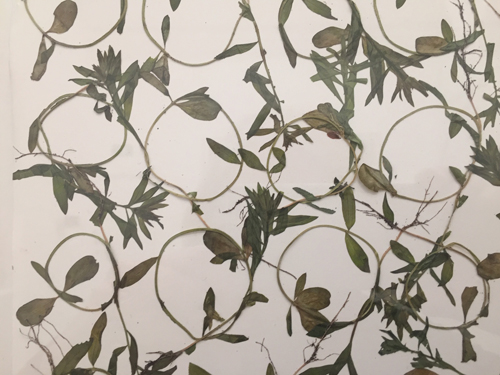

In the third room ‘Design for a farmer’s duvet’ (regrown 2019) follows from an invitation to make work with a co-operative of flax farmers in Dieppe, Northern France. John created compost into which he planted flax seeds given to him by one of the farmers, Franck Sagaert. When the seedlings were a few inches high, John plucked each one out of the soil, wound each plant and root into a circle and pressed them, generating the motif for a ‘design’. The completed piece was created by gluing each pressed plant in rows onto a large sheet of flax woven in France. The structure evokes the linear form of a script. It is also repetitive in the time-honoured way that designs repeat but it is anything but ‘designed ‘ in any determinate sense. A seed becomes a seedling and then becomes material for new life as an artwork. The pattern is cyclical and rhythmic as well as linear and developmental, unfolding like a story that we are invited to explore, but not literally read.

Script appears as a leitmotif in this work. In ‘A Language from the garden (Nymans language)’ (2017), exhibited in the second room, John invents an alphabet drawn from different species of trees in the gardens of Nymans, West Sussex. The National Trust, who now own and run this historic property, commissioned the work. The leaf of each species forms a letter engraved in marble. Nymans Language is also a downloadable font that the public are invited to use. Where normally the shape of the letters of the alphabet are simply a means to an end rarely noticed, Nymans Language draws our fascination through the significance of each leaf shape and a sense of play and discovery that is fundamental to the way we, as human beings, decipher meaning. We become the child who is excited when he or she learns to read. We share the thrill of the code breaker who ‘cracks’ a secret.

‘Soil Books’ (2019) in the third room of the gallery are a series of nine sculptures in which the content of each ‘book’ is made with leaves picked up each day as John walks from his house into his garden. “It’s like a ritual, so that every leaf in those books – the language of the books – is from my gardenâ€. Each ‘page’ is made of processed soil with leaves that are pressed, gilded and stained with watercolour and each book contains twenty pages of which only the middle two pages are displayed. We might never read the pages beneath the ones that are presented, but we come to know the labour that has led to their coming into being. This is a spiritual labour that evokes the monastic but in some strange reversal. The order of the books is crucial because it indicates the change of seasons. Instead of renouncing life to focus on the spiritual, this series of works reconnects us with mystery in everyday experiences. Cage shared a similar sense of mystery and used different tactics to reveal this: 4’33 “(1952) frames an interval of time in which we as audience are invited to encounter the sounds we make as human beings when we gather together. It appropriates the ritual of the concert and concert hall to open up to the life that exists beyond the frame just as John’s gathered leaves experienced through the frame of the book in Soil Books, make visible the unpredictability and sheer beauty of the life in one material encountering another. In the work of both artists we continually move between the human and nature, co-creatively.

This particular dynamic is deeply felt in the ‘Library of Ecological Conservations – Leaves and Me’ (2017-19) also in the third room. The work consists of 36 ‘letters’ composed over the course of three years in which the apparent artifice of gilding in silver, gold and copper from the ‘base ‘materials of leaves and paper made from compost manifests a present day alchemy. We sense the magic that is contained in this library displayed in three groups of 12 works. In each work the materials have undergone a transformation, creating a life of their own, one that John has nurtured into being through carefully judged constraints and a practice of care, firstly in each individual work and secondly in the placing of each work within its group of 12.These works breathe within their own space and yet combine to create an almost mystical whole. The vaulted upper floors of this particular area of the gallery can rarely have been so evocative of a medieval cathedral, inviting us to reach out for something beyond.

In the presence of such beautiful work focused on continuing nature’s processes, why do we have a final work that frames the need for reconciliation? The exhibition is entitled Dear Nature, a reference to an art work created in 2018 when John wrote a letter to nature every day for 81 days. Each letter begins with the recognition that human beings are degrading the conditions that enable us to live, a widening gap between ways of being that are incompatible and are indeed in need of reconciliation.

‘Dear Nature’, letter of 10th January, 2018.

Dear Nature

We have been lovers.

We made deities from your wonders

We worshipped you; laid our fears at your feet.

We thought that we needed you to need us.

But wasn’t that just some way of seeking control?

Maybe we find it hard to accept that you are the most powerful

and complex set of relationships that we can encounter; perhaps we got jealous of all your other affairs.

In our rush to evolve in our fights and flights, we have got lost among our own conceits; spinning such a terrible storm.

I am sorry.

What to do?

Yours

John

The downward spiral implied here from love to worship to control gets to the core of the question of what it is to know that we have profoundly affected our environment. Each work in the three rooms of the gallery addresses this question in distinctive ways. The exhibition also spills over into public space. In the square opposite the Ikon Gallery there is an office complex belonging to NATWEST bank. In front of the bank with its proud NATWEST sign, is a tree in which John has placed large but discrete metal lettering that follows the line of the trunk with the words “So Sorry….â€.

An apology is both the act of saying sorry for a wrong doing and the explanation and defence of a belief or system, especially one that is unpopular (Cambridge online dictionary). Dear Nature (2020) functions in the first way, saying sorry for the damage we have inflicted on nature and also in the second to expose problems of belief and practice that have led to our current predicament.

‘Dear Nature’, letter of January 15th, 2018

…

Our need for surplus focused attention on improving you, efficiencies melded in the pressures of a market. We wanted more and more from you; growing yields belied the damage we were doing.

We signed our name in your soils.

Perhaps we did not know of this but we do now. It is a cycle that shows us our deficiencies. It is us that need to improve. We can do better.

No more signing in your soil.

Yours

John

We have only described here a small sample of works in the exhibition. And no review can do justice to either the scope or the authority of this exhibition. It has been curated by an exceptional team at the Ikon Gallery under the directorship of Jonathan Watkins.

There are other exhibitions in the Ikon Gallery at the moment including, in the First Floor Galleries Judy Watson, an Australian artist of matrilineal Waanyi heritage, addresses Australia’s ‘secret war’ in relation to indigenous Aboriginal people and brutal forms of colonisation.

In the Tower Room of the second floor, Mariateresa Sartori (until 5th April, 2020) in which Chopin piano pieces are visualised as conversations between two people.

Yhonnie Scarce, who belongs to the Kokatha and Nukunu people in Australia, will open in the Tower Room on 9th March – 31st May 2020, exploring the political and aesthetic qualities of glass, in particular the crystallisation of desert sand as a result of the British nuclear tests in her homeland between 1956-63.

(Top photo: Installation view. Courtesy of the artist and the Ikon Gallery)

References

Feisst, S. 2009, “John Cage and Improvisation: an Unresolved Relationship,†in eds. Gabriel Solis and Bruno Nettl. Musical Improvisation: Art, Education and Society, Chicago: University of Illinois Press. pp. 38–51.

Newling, J., 2018. Dear Nature. Warwick and Nottingham: Warwick Arts Collection and Beam editions.

ecoartscotland is a resource focused on art and ecology for artists, curators, critics, commissioners as well as scientists and policy makers. It includes ecoartscotland papers, a mix of discussions of works by artists and critical theoretical texts, and serves as a curatorial platform.

It has been established by Chris Fremantle, producer and research associate with On The Edge Research, Gray’s School of Art, The Robert Gordon University. Fremantle is a member of a number of international networks of artists, curators and others focused on art and ecology.

Powered by WPeMatico