This post comes from the Artists and Climate Change Blog

In 2014, I wrote a play called Kill Climate Deniers. It’s the story of a group of eco-terrorists who take over Australia’s Parliament House during a Fleetwood Mac concert and hold the entire government hostage, demanding an instant end to climate change. It’s an action/hostage drama with a soundtrack of classic House and Techno from 1988-1992. The play was scheduled for a production with a company in my hometown of Canberra, Australia. We received $19,000 AUD from the local state arts council to do a script development of the work.

As soon as the funding announcement came out, a bundle of right-wing commentators (Breitbart, Infowars, and their Australian equivalents) expressed shock and outrage at the play’s title. A local conservative politician called for the funding to be revoked. It’s a tale as old as time: provocative (clickbait) artwork meets professional outrage merchants.

The script had been accused of “incitement†by its critics, who had threatened to turn us in to the police. This normally wouldn’t worry me, but the Australian government had recently passed new anti-terror legislation with unclear consequences. It is now illegal in Australia, for example, to incite terror through “reckless use of language.†What does that even mean, and would the play run afoul of it?

Following the burst of media attention, we had to make the hard decision of canceling the Canberra production. I sat down with director Julian Hobba and we made the brutal call that without real financial resources we couldn’t do the production justice, and more importantly, we couldn’t protect our creative team from online blowback. So we shut down the work. And then we went to work.

The next step was to meet with our lawyers. I hired a legal firm to go through the script line by line to make sure there was no material that could blow up in my face. Expensive—$2,800 AUD to get the whole thing vetted—but really interesting to get that legal perspective. (And cheaper by far than going to court.) Once I’d gotten the all-clear that there was nothing in the work that could land me in jail, the next step was to tackle the media-sphere. Before this play could ever be produced, there needed to be content in the public domain that countered the rhetoric being blown about by the outrage merchants and climate deniers.

We put together a package of other material: an album (with musician collaborator Reuben Ingall), a short film (with my brother Tom Finnigan), an ebook, and a website(with designer friends New Best Friend).

When I say “album,†what I mean is, we recorded the whole script as a radio play (directed by Julian Hobba). Then Reuben composed an album of techno bangers, in the style of classic early ’90s rave music, and sampled dialogue from the radio play the way dance music often samples dialogue from movies.

This all-digital content meant that anyone who wanted to could access the work, instead of relying on what journalists had previously written. Putting this together took thousands of hours of work throughout 2015-16, and the contributions of many friends and collaborators who volunteered their time.

I gambled on the notion that the little flare-up of controversy around the play’s funding would result in an audience for the digital material. I was wrong. The album and ebook had to build up an audience more or less from scratch.

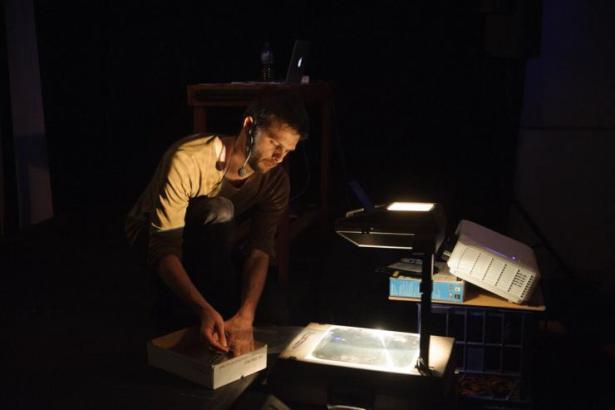

We started at the You Are Here Festival in Canberra in April 2016. We held a panel to talk about political art (and whether it should ever be government funded), and then had a no-holds-barred dance party DJed by Reuben to launch the website and the first single from the album. I also did a solo retelling of the work.

When the album came out in September, we launched it with a special listening party at Parliament House. Unescorted audience members walked through the House listening on headphones to an audio tour style version of the album, complete with gunfire and explosions, in the parts of the building where the story takes place. That was an interesting hook that garnered us some good coverage, so that if someone Googled Kill Climate Deniers, they wouldn’t just find a bunch of angry blather on Breitbart or Infowars. Now the ground was clear for a company to actually produce the script.

Clearing all that nonsense to one side, though, brought back to light two key issues that had been obscured in the back and forth with the right-wing media.

1. Is the play any good?

Controversy doesn’t mean you’ve written a good play. You can have a clickbait title and an attention-grabbing conceit, and have written a total piece of trash.

Some of my closest collaborators, the people whose opinions I trust more than my own, pushed me to keep forging ahead. First through the small amount of resistance, and then through a great deal of public indifference, they insisted that the work was interesting, funny, fun, and worth producing. They kept me pushing the project forward, finding new ways to animate the work and manifest it in the world. One of the points of having close collaborators is that you can trust them when you can’t trust yourself, so I did what they said, and finished the play.

In June 2017, the play was awarded the Griffin Playwriting Award. This September, it’s getting its first run in Long Beach, California, thanks to The Garage Theatre, in March 2018 it’s being produced by Griffin Theatre in Sydney. So, I’m telling myself that my friends weren’t wrong, it was worth it to persevere. But you never know for sure, and one of the ridiculous things about our art form is that you have to balance total conviction in your own practice with the deep certainty that you’re also a terrible writer and you’ve got a long way to go.

2. Is this play counterproductive?

Some very thoughtful people, including my mum, said that calling the play Kill Climate Deniers is needlessly antagonistic, reinforces tribalism and aggression between left and right, and does harm to the climate movement. This is what someone commented on a Guardian article about the show:

Unfortunately, the vast majority of people will react to the title, having never or being ever intentioned to watch the actual play…That’s how you unintentionally mess the world up in a direction that runs opposite to your initial objectives.

Is this true? Maybe. But how do you measure these things? Certainly, this work isn’t going to change anyone’s mind, but it was never about that.

Kill Climate Deniers uses the right-wing deniers to amplify the conversation around the work in order to access some of the many people who’d never come see a play “IRL,†but who might read an article about a “controversy.†Artists can’t control what happens in that media-sphere—the best we can do is ride the wave—but putting the work in that public space does put us in dialogue with a huge number of people we’d never have connected with otherwise. We don’t have to be pleading for column inches—we can be smart, we can make our own platforms, however compromised they may be.

I think, as artists, we can make the media work harder for us.

“But David, if most people reading about the work just hear a clickbait title and see some right-wing anger, aren’t you switching off people who might otherwise be productively engaged in climate activism.? Aren’t you worse off than when you started?â€

Maybe. Maybe. I don’t think so, I doubt it, but maybe.

Stay live to that possibility. Keep asking the question. Keep looking for evidence that you’re wrong. Keep being ready to change your mind, change direction if you need to. Keep trying. Keep focused.

Good luck to all of us, I think. Here’s a song for you.

______________________________

David Finnigan is a writer, theatremaker and pharmacy assistant from Canberra. He is a member of science-theatre ensemble Boho and an associate of Coney and the Sipat LawinEnsemble. David is a Churchill Fellow and an Australia Council Early Career Fellow. David is online at davidfinig.com.

Artists and Climate Change is a blog that tracks artistic responses from all disciplines to the problem of climate change. It is both a study about what is being done, and a resource for anyone interested in the subject. Art has the power to reframe the conversation about our environmental crisis so it is inclusive, constructive, and conducive to action. Art can, and should, shape our values and behavior so we are better equipped to face the formidable challenge in front of us.