This post comes from the Artists and Climate Change Blog

As climate changes continue to impact upon the world, we as a species will need to create truly resilient systems for humanity to live in the natural world with more consideration. An excellent starting point could quite simply be to begin reconnecting with where our food comes from, how it is produced, and what we do with the waste. Thus, as an artist and anthropologist I began to consider ways in which I could find out more about how connected and aware our communities are of the food systems that sustain them.

In January 2018 I presented the creative installation Food for Thought at Rainbow Serpent Festival, an internationally-renowned festival drawing over 20,000 people for a four-day weekend of music and creativity in the Victorian bush in Australia. The installation sought to engage festival goers into dialogue about fresh food consumption and waste practices. I asked: Where does your fresh produce come from and where do you put the waste? The bigger question behind this is, of course, how we can achieve sustainability and resilience within our food systems.

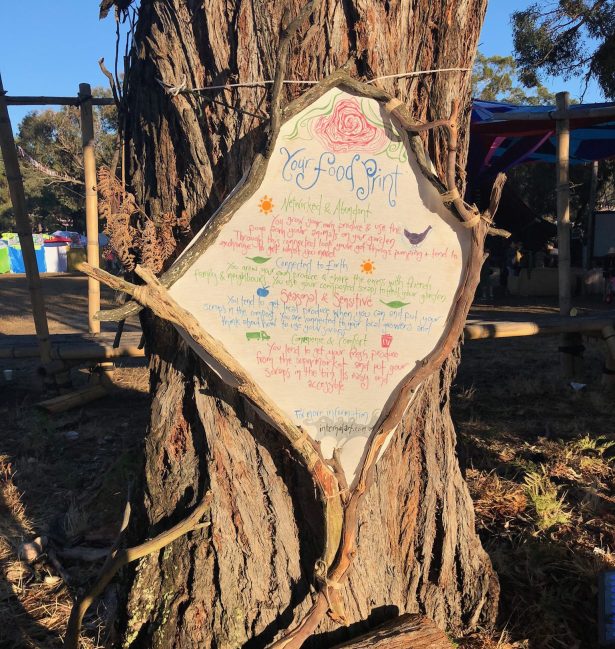

The installation consisted of seven “pods,†each a little over 5-feet tall, with ribs made from marine grade ply, a middle hoop and a mesh fabric skin, hung from trees, lit up at night, and set in sympathy to the site. Natural and found objects were used to construct a walking maze around the pods, which represented different sites of fresh food purchase and waste disposal commonly used by people. In the centre, the earth pod showed four common consumption profiles that you could match your own food print to.

The food mapping installation seeks to provoke and make conscious questions about food consumption and our relationship with the natural world. Inside each of the source pods is information about how far your food has travelled to get to you. Each of the waste pods contains information about what happens to the waste and how it breaks down. Participants were asked to answer a simple question by clicking a hand counter inside the pods. Icons then allow participants to get a sense of their own food print profile from the accompanying information board. You can see more on the food prints here if you want to explore your own.

Our creative research method crosses the disciplinary boundaries of artistic practice and social research. As an interactive installation, the work has an educational and research basis grounded in empirical evidence. Part of the beauty of researching via art is that the piece was specifically designed to inspire curiosity and play, conversation and contemplation, while asking simple survey questions that allowed us to illustrate the consumption and waste practices of festival goers. Alongside this, my collaborators and I collected ethnographic insights on the kinds of conversations and experiences people shared with each other while engaging with the installation.

We estimate from the observed interactions and survey data that around 5,000 people actively engaged with the research side of the project. Throughout the long weekend, we witnessed numerous types of interactions ranging from vague acknowledgements that a pod was hanging down and needed to be sidestepped, to people settling down within the space and actively engaging with the work. Children ran through and around the installation, spinning the pods so that the tendrils splayed out to reveal the openings, leading to further interaction. We overheard people discuss their consumption and waste practices with others, and reflect on how their food print influenced their lifestyles. I also witnessed a grown man hanging and swinging off one of the pods – not the ideal behavior an artist wants to see in relation to their work, but it was good that the pod was robust and resilient enough to take it.

A key finding of the research to date is the sense of guilt and shame felt by many people. Working with Dr. Alexia Maddox and other collaborators, I have run three Food for Thought creative interactive research data collection installations, with the installation at Rainbow Serpent Festival being the latest iteration. High levels of consumption guilt (not linked to behavior change) became apparent in the first two installations. The data collection process in each of these installations asked participants to input their responses to the questions by using a potato or carrot stamp with egg tempura ochre paint onto a collaborative canvas. The first installation was in a gallery and featured a large community created artwork. The second installation took place at a market stall where children and adults alike added their potato or carrot ochre stamps to the initial collaborative piece. At both events, we occupied the installation space and struck up conversations with people about the work. The shame or guilt became known when participants made their marks on the canvas, along with statements like “I wish I could say that I do differently, but I shop at the supermarket and I dispose of the organic waste in the rubbish bin.†On occasion, people would express that they felt as though they had little control over these patterns of consumption and waste. These insights have led us to other questions about how we can, as a society, make it easier for people to behave in ways that they know are good for the planet. This finding on consumption guilt obtained in the first two installations was cemented for us during the festival weekend.

This mobile practice and multi-site installation work is part of a long-term research project that I hope to bring to a variety of places. The purpose is to collect representative data from people across the greater Melbourne region to creatively map fresh food consumption and waste patterns. The final component of the installation will draw together the other creative works, including my large-scale paintings of vegetables, into a collective installation.

Human interaction and perception of the natural world are common themes in my work. As an artist and anthropologist, I thoroughly enjoy the merging of the two disciplines. My new works aim to focus more upon memory spaces, value systems, and the ways in which humans engage with the natural world be it through resource extraction, waste production, or recreational activities. By designing creative low-tech interactive art installations, I ask for contribution from participants in order to stimulate thought and conversations, and encourage input on how we as a species relate to the natural world. Hopefully, this will unearth new and positive ways to relate to the planet that are reflective of different ontological understandings of the natural world.

______________________________

Dianna Tarr is an artist and anthropologist located in the Yarra Valley, east of Melbourne, Australia. Informing her creative practice is a deep interest in the ontological understandings of cultural relationships with the non-human, other, life, and the natural world. She explores ways to stimulate thought, response, and action through creative research methods that encourage conversation about some of the world’s most “wicked†problems. Dianna has been awarded numerous grants for creative research and has exhibited extensively over the last twenty years.

Artists and Climate Change is a blog that tracks artistic responses from all disciplines to the problem of climate change. It is both a study about what is being done, and a resource for anyone interested in the subject. Art has the power to reframe the conversation about our environmental crisis so it is inclusive, constructive, and conducive to action. Art can, and should, shape our values and behavior so we are better equipped to face the formidable challenge in front of us.