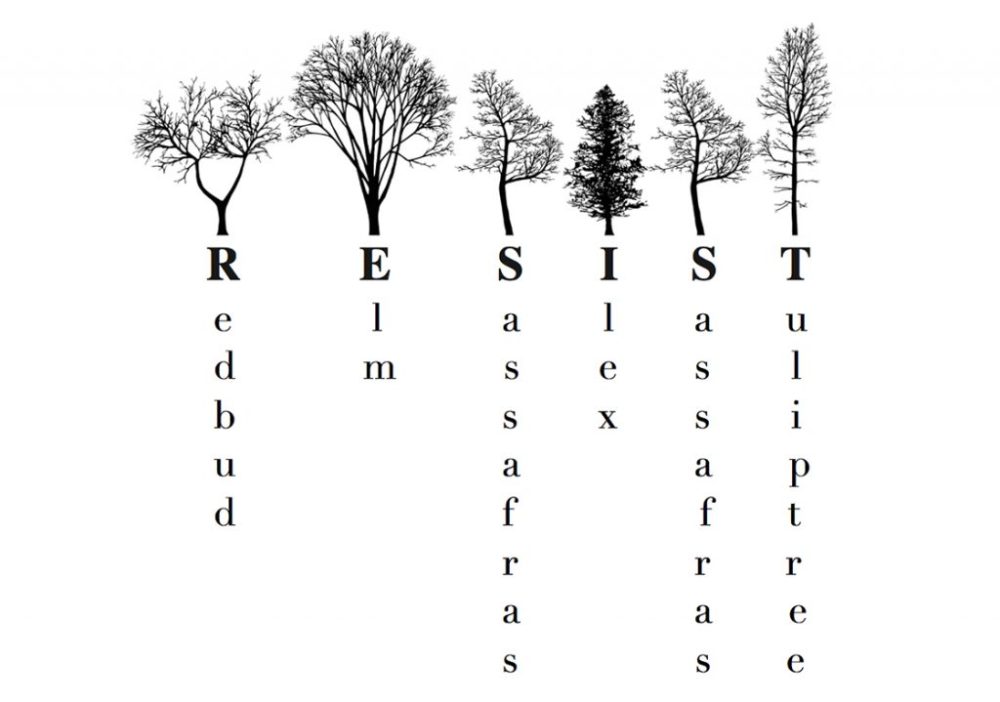

This month I have for you a fascinating interview with Katie Holten, a visual artist and self-proclaimed “resistance fighter†based in New York City. She’s the creator of the New York City Tree Alphabet, an interactive project that lets you type in trees. Really!

What is the New York City Tree Alphabet?

The New York City Tree Alphabet is a new ABC. Each letter of the Latin alphabet is replaced by a drawing of a tree from NYC Parks’ existing native and non-native trees, as well as species to be planted as a result of the changing climate. For example, A = Ash, B = Birch, C = Crabapple. It’s a font and an alphabetical planting palette, allowing us to plant living messages with trees. I wanted to create something beautiful, accessible, and fun, but also practical (it’s a planting guide), serious (it deals with New York City’s changing climate), and ridiculous or curious (why on earth write with trees?!).

What inspired the project?

Oh, many things. The project didn’t grow from a single seed; it has many roots, many branches.

Does it grow out of your 2015 book About Trees (Broken Dimanche Press)?

Yes! I made a Tree Alphabet so that I could translate texts into trees. I wanted to create a language beyond the human. I’ve always been fascinated by the inextricable relationship between humans and nature, the problematics of language, the fact that we are nature. By using words we create a divide, an invisible barrier separating one from the other. When we name things we confuse the name for the thing. I was interested in transforming words into something not-quite legible, forcing the reader or viewer to really think about the individual letters, characters, words, names. It was only after I made the book, About Trees that I realized that the Tree Alphabet could be used in real life as a planting guide.

How do you hope people use your alphabet?

Part of the fun is not knowing what possibilities others will see in it and what may emerge. But I hope that people will share some heartfelt words and messages with us so we can select some to plant around New York City with real trees. We’re hoping to start the first phase of planting as soon as April 2019.

Have you received a response yet?

Since first sharing the Tree Alphabet in January we’ve received words, poems, short stories, and simple thank-you messages, written in Trees. A few people told me how twenty minutes slipped by while they played with the alphabet. Imagine if we all had twenty minutes a day, or even twenty minutes a week, to think in Trees. I’ve also had requests to share it with children in classrooms and to go for nature walks in city parks. I was at the Children’s Museum of the Arts a few weeks ago and we had great fun screen printing the Tree Alphabet. All those kids got to take home their own prints of the alphabet, so hopefully it’ll live on in their bedrooms and inspire tree dreams and branching thoughts that will lead who knows where. Most of the kids wanted to see their name written in Trees, so that was our first exercise. But I hope that with older children and with more time for conversation, we can start thinking about what other words – dreams, hopes, memories, love letters, stories – we could share with Trees.

The NYC Park Rangers are also excited to create Adventure Guides using the alphabet that they’ll share at all the city’s Nature Center’s this summer. That should be a fun way for kids and families to read the landscape, creating and solving puzzles by reading and writing with Trees. Who knows what they might discover!

The Tree Alphabet isn’t your first alphabet. What draws you to the artistic use of ABCs?

I’ve worked with language for years, but never in such a finite way. I’d never created a complete or closed written system like this before. It’s definitely a political project. It grew from the confusion around simple daily language. Facts and truth don’t seem to mean anything anymore, or are being twisted into all kinds of ugly, distorted realities. I created my first Tree Alphabet back in 2014-2015, so my feelings about this have only gotten deeper and darker since then. I felt compelled to create something beautiful that speaks the truth. Trees can’t lie.

In 2016 I was invited to work at the Camargo Foundation in Cassis, France and immediately realized that the limestone I was studying was telling stories. I wanted to read and write the stones. The Stone Alphabet emerged. It’s a very different kind of alphabet project – it’s infinite; there’s no ABC. Whereas the Tree Alphabets are figurative and “readable,†the Stone Alphabet is abstract. I should also mention that my sister had identical twins in 2013, so I discovered the wonderful world of baby books. It can’t be a coincidence that a year later I started making my own ABC’s.

Thinking about them, the next generation – Generation Anthropocene – has been profoundly disturbing. What are they going to have to cope with when they’re my age, and how will they cope? Education is so important, so it seems like the simplest, most basic thing we can do for ourselves and for our kids is to create new ways to read the world. To read a world beyond the human. We’re the monster destroying everything. We need to learn to see with others’ eyes, to understand that we’re only a tiny part of this large web and everything else here on Earth is also living, breathing, communicating.

What are your thoughts on the role that art can play in activism?

Art is a way to make sense of the world. For me, my work has always been a research project. I’m fascinated by how things work, always questioning things, trying to understand how one thing relates to another thing, where we fit into it all, trying to draw out underlying and/or invisible patterns that create meaning in all the seeming randomness. My work has always been political, but often not in a loud way. I like to leave everything open for the viewer to read themselves and come up with their own answers. But since the US election everything’s been turned inside out. Since 2016 I’ve been carrying words of Resistance with me every single day. It’s exhausting, but I can’t imagine not carrying some sign of Resistance, of Persistence. I wear ribbons and buttons that are hand-made by other artists. It freaks me out that most everyone else looks so normal, no sign that anything super freaky and fucked-up is going on. We’re living through a national and global emergency, but you’d never know it by the way people look.

I think art is necessary to start conversations and provoke discussion and create change. I’ve been invited to show in museums and biennales, and that’s wonderful, but it’s real-world conversations that mean a lot to me and feel real. We need to understand what we’re doing as a species. It’s critical. For years, decades now, I’ve been grappling with how to create real change. I’ve worked with scientists and climate scientists, participated in conferences and symposiums, and all too often the artists (despite the scientists’ best intentions) are expected to produce beautiful, engaging illustrations of climate science. This serves a purpose; I think newspapers and news outlets need more and more of this. But, is it too little too late? What can I do to make a difference? My partner Dillon Cohen and I started having more formal conversations with a community of activists in NYC and that led to our Sunday Salons.

What are the Sunday Salons?

They’re monthly gatherings hosted by me and Dillon at our loft in Union Square to discuss the possibilities for Art and Activism in the Anthropocene. We started them in 2014, inviting a small group of friends and colleagues who were also grappling with the issues. Guests have included writers, activists, climate scientists, curious thinkers. Roy Scranton shared work-in-progress from his book Learning to Die in the Anthropocene, Jennifer Jacquet introduced us to the power of shaming, we looked at deep time, geo-engineering, genetic modification, love in the Anthropocene. Every conversation seemed to circle back around to the need for new stories, a hunger for storytelling. All this definitely fed into my tree alphabets and the book About Trees. For a few years we were holding the Salons regularly, once a month on Sunday afternoons. But the last year I’ve been on the road a lot and our building is under construction, so we’ve had to pause them, unfortunately. The Sunday Salons are a safe space where we can gather to share our fears and hopes and discuss action. In a way, the Tree Alphabet, grew from the Salons. We’d only had one or two salons when I had a moment of clarity (in the middle of the night, of course!) and realized my tree drawings could replace letters, trees are characters, they can slow us down and share their truth with us.

What’s next for you?

I just arrived at MacDowell, so I have the luxury of space and time and silence to read, read, read, catch up with myself, breathe, breathe, breathe, and walk in the trees. I’m finishing up a few projects, including a Stone Alphabet (Field Guide to Manhattan) for the next issue of Emergence magazine, on the theme of Language. I’m also working on a new book, a sister to About Trees, using the New York City Tree Alphabet. I’ve also been invited to develop a new Tree Alphabet into a children’s picture book, so that’s very exciting! When I get back to the city in April we hope to begin planting messages in trees, so I’m busy trying to resolve questions of signage.

Email your work, poem, dream, love letter, or message – in trees! – to Katie at studio@katieholten.com and read more about her work at her website.

(Top image: New York City Tree Alphabet by Katie Holten, 2019.)

This article is part of the Climate Art Interviews series. It was originally published in Amy Brady’s “Burning Worlds†newsletter. Subscribe to get Amy’s newsletter delivered straight to your inbox.

___________________________

Amy Brady is the Deputy Publisher of Guernica magazine and Senior Editor of the Chicago Review of Books. Her writing about art, culture, and climate has appeared in the Village Voice, the Los Angeles Times, Pacific Standard, the New Republic, and other places. She is also the editor of the monthly newsletter “Burning Worlds,†which explores how artists and writers are thinking about climate change. She holds a PHD in English and is the recipient of a CLIR/Mellon Library of Congress Fellowship. Read more of her work at AmyBradyWrites.com and follow her on Twitter at @ingredient_x.

———-

Artists and Climate Change is a blog that tracks artistic responses from all disciplines to the problem of climate change. It is both a study about what is being done, and a resource for anyone interested in the subject. Art has the power to reframe the conversation about our environmental crisis so it is inclusive, constructive, and conducive to action. Art can, and should, shape our values and behavior so we are better equipped to face the formidable challenge in front of us.

Go to the Artists and Climate Change Blog

Powered by WPeMatico