This post comes from the Artists and Climate Change Blog

A quick Internet search for the world’s windiest cities suggests that Wellington, New Zealand, is the most tempestuous: its average annual wind speed is 26.7 km/h (16.6 mph). Close runners-up include the cities of:

- Rio Gallegos (Argentina) – 25.7 km/h (16 mph)

- Saint Johns, Newfoundland (Canada) – 24.3 km/h (15.1 mph)

- Punta Arenas (Chile) – 23.3 km/h (14.5 mph)

But despite their blustery reputations, none of these famously windy cities has honored the wind gods with a museum dedicated to the wind. For that, you have to travel to the magical city of Trieste, the architecturally stunning seaport in northeast Italy at the head of the Adriatic, tucked inside the Slovenian border. The city James Joyce called home for 11 years.

Not only have Triestinos embraced the cold north winds that define their city, they discovered, way back in 1999, how to capture the wind: Bora in scatola. Once captured, the wind began to work its magic, and soon afterwards, Rino Lombardi’s dream of creating the world’s first wind museum – Museo della Bora – was born. A humble home for the most mischievous, volatile and invisible of elements, in which we spend our entire lives.

Rino Lombardi, founder and director of the Museo della Bora, carefully releasing the bora from a can of “bora in scatola†(wind in a box).

A professional copywriter with a dry sense of humor, Mr. Lombardi opened, in 2004, a temporary home – magazzino dei venti – for the restless and impetuous bora. “She is free and easy; she is not willing to remain trapped,†he explains. “She wants to steal hats, snap umbrellas, overturn trash bins and cars, sink boats, and roar at the trees. The only way to calm her is to give her a stage all her own.†And so, the search for a larger and permanent home for the Museo della Bora continues.

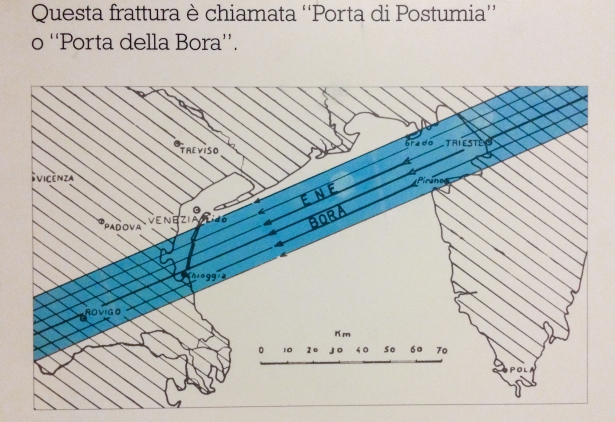

Nota bene: bora (μπόÏα) derives from Boreas, the Greek god of the north wind, whose windswept hair and beard were tinged with ice and snow. Meteorologically, the bora describes the cold east-northeasterly (ENE) katabatic winds that sweep down from the foreboding limestone Karst plateau, and descend rapidly – sometimes violently – towards the Adriatic coastline. Trieste is right in its path.

Currently located on Via Belpoggio, the Museo della Bora’s magazzino is literally bursting at the seams with sculptures, kites, weather vanes, anemometers, miniature windmills, wind socks, crampons, pinwheels, whirligigs, flags, hats, maps, poems, postcards, posters, paintings, photographs, cartoons, newspaper clippings, books, documentary films, audio and video recordings. Collectively, these found / donated / purchased objects illustrate the infinite ways our lives are touched and shaped by the wind: mythical, historical, cultural, political, architectural, meteorological, literary, journalistic, artistic, technological or just plain whimsical.

“Like any self-respecting museum,†said Mr. Lombardi, tongue in cheek, “the Museo della Bora has several collections.†He walked me through each collection, crowded impossibly into a 60 square-metre space that is at once fantastical and fascinating. At times, I felt like a child again, filled with awe at the craziness of it all. Crazy and alive like the wind.

The most popular collection seems to be the ever-expanding wind archive: bookshelves and display cases overflowing with jars, bottles, pots and cans; each one contains a unique sample of wind collected by wind lovers from the four cardinal directions. The majority of these bottles arrive by the post, with hand-written notes attached documenting the date and place of collection: Halifax, Oslo, Mount Fuji, Chicago, Padua, Rio. My bottle of Québec’s westerly winds – carefully sealed inside a Christmas tree-shaped bottle no less! – has just been mailed. When it arrives in Trieste, I will join the prestigious ranks of other “wind ambassadors†whose bottled donations make up the Museo della Bora’s eclectic wind archive.

For history buffs, the archive of Silvio Polli, considered one of the world’s leading experts on the bora, is a treasure trove of old black and white photographs, newspaper articles, scientific publications and meteorologic instruments. This archive was donated by the Polli family to the Museo della Bora.

One of the many antique anemometers in the Museo della Bora’s collection.

I particularly love the museum’s collection of Roberto Pastrovicchio‘s black-and-white photographs of broken umbrellas abandoned in the streets of Trieste, umbrellas that obviously had displeased Boreas for one reason or another. With his project Analisi Catabatica (Katabatic Analysis), Pastrovicchio attempts to create an “aesthetic catalogue†of the bora through its impact on everyday objects.

Roberto Pastrovicchio. Analisi Catabatica #03 / data 20.11.2011 / ora/hour 15.30 / velocità raffica / guts speed 91,08 Km/h. Reprinted with permission.

But I am saving the best for last. The Museo della Bora’s most impressive collection, in my humble opinion, is the library that Mr. Lombardi has lovingly curated over the past 20 years. So many books about my muse in one place! Art, architecture, history, fiction, poetry, mythology, meteorology, renewable energy… Don Quixote tilting at windmills; the poems of Umberto Saba; architectural techniques to funnel wind into buildings in order to provide natural air conditioning; the history of French weather vanes; several university theses.

This library would be an invaluable resource for artists in residence, especially those researching the question: how have artists represented the invisible through the ages? As one example, see Zephyr and Aura gently blowing Boticelli’s Venus to shore on the cover of Il Libro del Vento, an incredibly beautiful book by Italian art historian Alessandro Nova. This is but one of the more than 400 titles in the Museo della Bora’s documentation center.

The cover of Alessandro Nova’s Il Libro del Vento, one of the more than 400 titles in the Museo della Bora’s collection.

In addition to founding and directing the Museo della Bora, Mr. Lombardi is the regional coordinator of the National Association of Small Museums (Associazione Nazionale dei Piccoli Musei), for Italy’s Friuli Venezia Giulia region. Over a glass of hugo, the popular Triestien cocktail of elderflower, prosecco, mint, and lime, he shared his vision for this small museum: to encourage the free circulation and exchange of scientific, artistic, cultural and social ideas. In this way, Mr. Lombardi hopes that the bora can be used as a metaphor for opening borders.

Given the European Union’s current refugee crisis, this is an extremely pertinent point. And it will no doubt become even more salient as climate migrants begin to abandon their homelands due to crop failure, sea level rise or extreme weather.

Museo della Bora is still a work-in-progress. But don’t let that stop you from visiting. Schedule your visit in early June, to participate in the annual Boramata, Trieste’s city-wide celebration of its most famous citizen. Or, schedule your visit between November and February in order to experience the bora, like James Joyce, in all its fury. “For my part I love the bora,†wrote Joyce. “It acts on me as a spirit of health that brings air from the sky.â€

Visits to the Museo della Bora’s magazzino are by appointment only. Be prepared to be carried away by Mr. Lombardi’s enthusiasm, by the bora, by the magic of it all. The Museo della Bora is a rare gem.

______________________________

Joan Sullivan is a renewable energy photographer based in Québec, Canada. Since 2009, Joan has focused her cameras (and more recently her drones) exclusively on the energy transition. Her goal is to create positive images and stories that help us embrace the tantalizing concept that the Holy Grail is finally within reach: a 100% post-carbon economy within our lifetimes. Joan collaborates frequently with filmmakers on documentary films that explore the human side of the energy transition. She is currently working on a photo book about the energy transition. Her renewable energy photos have been exhibited in group shows in Canada, Italy and the UK. You can find Joan on Twitter and Instagram.Â

Artists and Climate Change is a blog that tracks artistic responses from all disciplines to the problem of climate change. It is both a study about what is being done, and a resource for anyone interested in the subject. Art has the power to reframe the conversation about our environmental crisis so it is inclusive, constructive, and conducive to action. Art can, and should, shape our values and behavior so we are better equipped to face the formidable challenge in front of us.