This post comes from the Artists and Climate Change Blog

Back in the days when I was still working for Cape Farewell in London, the appetite for artistic engagement with climate change seemed to be everywhere, including in the big cultural venues: from Ten Billion, the shocking science-lecture-performance at the Royal Court, to programs at the Science Museum and the Tate. The prevailing attitude focused on raising awareness about global climate change, and asking questions about what was happening in our own backyards. How much insight did we have into the carbon footprint of these grand buildings? Ambitious productions, touring and attending conferences and Biennale all over the world – greening our own practice was just as (or even more) important as raising awareness about melting glaciers. And here the amazing ladies (mostly ladies) of Julie’s Bicycle jumped to help.

Since 2012, all cultural organizations that receive regular funding from Arts Council England are required to report on their environmental impact, using Julie’s Bicycle Creative IG tools – advanced carbon calculators designed specifically for the cultural sector. This has made Arts Council England the first arts funding body to recognize the environmental role that the cultural field can play. Museums, theatres, festivals, tours, galleries and productions started to reduce their carbon emissions (as well as water use and waste) as it was made fun and clear how to do so. See below a Top 10 list of my favorite art organizations talking the talk and walking the walk – with several gems from Scotland!

1. Open Jar Collective

The collective of socially engaged artists and designers that form Open Jar Collective operates mostly out of Scotland and actively share food, ideas and possibilities for change. Always involving the local community in their workshops, dinners and debates, they are re-thinking and re-shaping Scotland’s food future. Make sure to check out their project Soilcity, where the collective offered explorations of soil culture through the alchemy of composting, growing, foraging, fermenting, brewing and cooking.

We use food as a vehicle for bringing people together, as a common language to understand the global economic system, and as a tool for exploring people’s fundamental relationship to the land.

—Open Jar Collective

Human Sensor, Kasia Molga, 2016. Photo by Nick Harrison, courtesy of Invisible Dust.

2. Invisible Dust

Reporting every day on the level of air pollution in London, Invisible Dust aims to making the invisible visible – particularly environmental challenges that don’t necessarily register to the naked eye. This awareness is brought through artists’ commissions, events, education and community activities. One of their exciting new projects, Under her Eye, features the amazing Margaret Atwood (amongst other ubercool ladies) in a summit on Women and Climate Change at the British Library this summer.

I love working with Invisible Dust – it’s a fantastic platform for collaborations between artists and scientists who are natural collaborators; both are explorers and storytellers, seeking out new ways of understanding, communicating (and indeed, changing) the world around them. So when it comes to the dry (and let’s face it, often frankly terrifying) language of climate change, the marriage of the two can be particularly effective. Artists can respond to environmental data in work that provokes real engagement – and scientists in turn can consider more creative and impactful ways of sharing (or indeed conducting!) their research. By communicating these urgent issues in lateral, innovative ways, by using humor and humanity, these sorts of works can reach us on a more animal, cellular, level – and therefore, hopefully, demand our response.

—Lucy Wood

3. Creative Carbon Scotland

Inspired by the ladies at Julie’s Bicycle, Creative Carbon Scotland supports Scottish arts organizations with training in carbon measurement, reporting and reduction. Though their work involves a lot of strategy and policymaking, the direct involvement of artists remains key. Projects such as The Green Tease, but also various themed residencies, allow for a good relationship with the local community and places artists in both arts- and non-arts organizations.

We believe that the things artists know and the way they think and do things has a contribution to make to changing the way we organize our society, which will help move it towards a more sustainable future.

—Creative Carbon Scotland

4. Grizedale Arts

Tucked away in the beautiful English Lake District, Grizedale Arts is a self-proclaimed “curatorial project in a continuous state of development.†The site, called Lawson Park, is a productive farm (which includes livestock), where artists can’t be afraid to get their hands dirty. The program, consisting of events, projects, residencies and community activities, engages with the complexities of the rural environment. Grizedale is the type of place where process is valued over product, and the boundaries of what an art institution can be (or ought to be) go wildly beyond the established structures and the idea of the white cube. Bring your wellies.

I want to broaden the idea of what art is and how it works; it is fundamentally the connective tissue that energizes all of our activities. It is an action, not a product, and everyone uses it. I help artists and communities make better use of one another, opening creative processes for both parties, helping both parties escape the confines of what can be a horribly narrow mindset. I aim for a way of living that is connected, a level body of resources built around fundamental elements, a real world of growth, cycles and change.

—Adam Sutherland

Professor Jaeweon Cho in the Science Walden pavilion during the first phase of the project, 2016.

5. Centre for Contemporary Art and the Natural World

Now part of a family of art and ecology organizations, which includes art.earth at Dartington Hall in Devon, CCANW is an educational charity which brings together curators, artists and researchers (myself included!) to give people a deeper understanding of their responsibilities within nature. Its Soil Culture project (2013-16), organized collaboratively with Falmouth University and RANE, was comprised of a research phase, an artist residency and a touring exhibition, and aimed at deepening public understanding of the importance of soil. It became the UK’s most substantial contribution to the United Nations International Year of Soils.

In the coming years, we hope to encourage a new generation of artists and curators to engage more people with the urgent ecological challenges we face globally. We believe that the arts can effect change in ways that complement the work of conventional education and science.

—Clive Adams

6. ONCA

ONCA, a gallery and performance space in Brighton, has an interesting founding story. It has to do with ONCA founder Laura Coleman meeting a puma in Bolivia. She connected with the puma, who had been a pet until it came to the refuge where Coleman met it when it was ten months-old. The puma, called Wayra, was terrified of the jungle. Over the years, Laura developed a friendship with Wayra, learning more from this cat about trust, patience and love. In 2011, Laura came back to the UK wanting to find a way to tell Wayra’s story, intertwined with the stories of all the other animals (human and non-human) she met in the jungle. ONCA is therefore an art space dedicated to performance and storytelling about issues that affect animals.

We work really hard at ONCA to provide a space, and a support network, for artists, young people and the general public to explore, question and creatively reimagine the world. We ask ourselves, how do we “stay with†social and environmental justice, in all their entanglements? How can art, and art spaces, contribute towards better nows, and better futures, for all?

—Laura Coleman

7. Deveron Projects

“The town is the venue†describes the framework of Deveron Projects’ work, as they inhabit, explore, map and activate the place through artist-driven projects. These projects may cover a variety of topics from employment to health, from ecology to architecture, from history to spirituality, and from migration to being local. They bring together people from all walks of life through public gatherings, symposium, forums, workshops, farmers markets, seasonal cafés, music events, street festivals, slow marathons, gardening sessions, traditional ceilidhs, internet conferences and Friday lunches. The 50/50 principle is their guideline for a socially engaged work practice: balancing artistic endeavor with everyday life.

Our town, like many rural places is facing the signs of globalization with shops, banks, services closing. We need to join forces and think of responses for creative regeneration.

—Claudia Zeiske

First Draft Ale was the catalyst for the first homemade malt organic ale in the last 500 years. Initiated by Futurefarmers, in collaboration with the Liberation Brewery. Photo: The Morning Boat.

8. The morning boat

The Morning Boat (Jersey, Channel Islands, UK) is a program of public art projects, exploring and reflecting on agricultural and fishing practices in Jersey and the impact these have on people’s lives. At the centre of the program is an international artist residency, inviting artists from around the world to collaborate with local farmers, fishermen, politicians, chefs, retailers and consumers, to encourage public discourse on complex critical issues that are central to the island’s economy, social fabric and way of life. Projects aim to be catalysts for positive change and cultural shifts, promoting best practice and creating new infrastructures. They negotiate social, political and environmental challenges, to encourage a more responsible and sustainable way of living and consuming.

All aboard!

On a small compact island, in which the urban, suburban and rural, merge, overlap and rub together, the production processes behind our consumption (and comparative wealth) are strikingly evident and immediate. Within this revealing landscape, the local and global are entwined together, as local industries facilitate, influence and respond to international developments. Despite this microcosm, or perhaps because of it, there seems to be a lack of sustained public debate regarding the practices and accountability of island industries and a defensive attitude towards critical voices that interrogate the status quo. The local phrase, “if you don’t like it, there’s a boat in the morning,†encapsulates this attitude, a mindset that holds back progress and the ability to creatively reimagine the way we do things.

—Kaspar Wimberley

Image Credit: Performance A Play for the Parallels by Lina Lapelytė during 7th Inter-format Symposium at Nida Colony, 2017. Photo by Andrej Vasilenko

9. Scottish Sculpture Workshop

Located in the foothills of the Grampian Mountains, in the rural village of Lumsden, Scottish Sculpture Workshop promotes a dialogue that considers the place of this rural locale within a globalized society. They are an active bunch, organizing residencies, Reading Groups, talks and lots of courses, including woodworking and ceramics. Make sure to check out their latest open call with DIY, an opportunity for artists working in Live Art to conceive and run unusual training and professional development projects for other artists.

Environment is deeply rooted across all our thinking, work and partnerships. We approach this not as a single issue but as part of the complex web of ecological, social, historical, economic, and political phenomena. Through networks such as Frontiers In Retreat we aim to be part of the global cultural shift that moves away from exploitative and extractive relationships with nature and instead work with artists to imagine, inspire and ignite new ways of being in the world.

—Sam Trotman

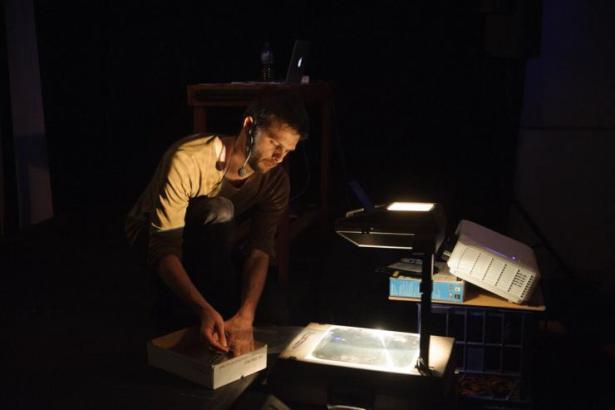

HeHe, Fracking Futures, 2013. Commissioned by Arts Catalyst and FACT.

10. Arts Catalyst

Through its continuous work with artists, scientists, communities and interest groups, Arts Catalyst commissions and produces large-scale projects, artworks, and exhibitions that connect with other fields of knowledge, expanding artistic practice into domains commonly associated with science and specialist research. They also commission research and are great advocates for cross-disciplinary thinking and working. They have worked with some of the biggest names out there (think Tomas Saraceno or Jan Fabre) and their list of collaborators is as extensive as it is impressive.

Arts Catalyst promotes new artistic practices, ideas, and ways of inquiring into the world. We work with artists, scientists, and people from myriad backgrounds and perspectives to create imaginative, inspiring, engaging projects addressing important issues of our time, from extractive capitalism and climate change, to histories and representations of race and migration’.

—Nicola Triscott, CEO/Artistic Director

(Top image: Duke of York Column. Photo by Kristian Buus. The string of LED’s wrapped around London’s main columns marked a future in which sea level rise has changed the landscape beyond recognition. This project was part of the series of interventions coordinated by Artsadmin.)

______________________________

Curator Yasmine Ostendorf (MA) has worked extensively on international cultural mobility programs and on the topic of art and environment for expert organizations such as Julie’s Bicycle (UK), Bamboo Curtain Studio (TW) Cape Farewell (UK) and Trans Artists (NL). She founded the Green Art Lab Alliance, a network of 35 cultural organizations in Europe and Asia that addresses our social and environmental responsibility, and is the author of the series of guides “Creative Responses to Sustainability.†She is the Head of Nature Research at the Van Eyck Academy (NL), a lab that enables artists to consider nature in relation to ecological and landscape development issues and the initiator of the Van Eyck Food Lab.

Artists and Climate Change is a blog that tracks artistic responses from all disciplines to the problem of climate change. It is both a study about what is being done, and a resource for anyone interested in the subject. Art has the power to reframe the conversation about our environmental crisis so it is inclusive, constructive, and conducive to action. Art can, and should, shape our values and behavior so we are better equipped to face the formidable challenge in front of us.

As a photographer focused on the energy transition, I would have liked to see here the inclusion of “nature’s free gifts of energy†– solar, wind, geothermal, water – as an essential element of Freespace. After all, architects and architectural firms around the globe are already

As a photographer focused on the energy transition, I would have liked to see here the inclusion of “nature’s free gifts of energy†– solar, wind, geothermal, water – as an essential element of Freespace. After all, architects and architectural firms around the globe are already