This post comes from the Artists and Climate Change Blog

In my recent projects, I have undertaken art-science investigations where a fusion of creative and scientific sensibilities can result in new ways of knowing and enable the emergence of novel approaches to creative inquiry where art and science are on equal footing for research – art informing science and science informing art.

With the overwhelming inundation of complex data, to find our way in the saturated drift that has re-characterized the ecological world, we must explore the possibilities of new sensoria to elucidate meaning and compose and configure accessible and novel interpretations.

My approach in these transdisciplinary investigations has been to facilitate access to new sensoria (sound, image and tangible interactions) to unveil innovative realizations, associations and insights into the fragility of ecological and biological patterns and conditions. These projects have creatively examined the concepts of the re-narration of extinction, the emergence of life, biological time and the essential links of bioculturalism to man’s cosmological placement.

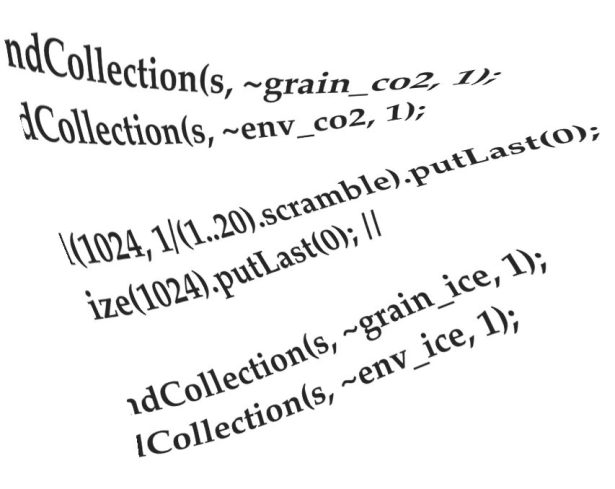

The bio- and ecoinformatic data sources I work with can be from my field sampling, from sources shared with collaborating scientists or from open source public databases from the US, Europe or Asia. Initially my projects build up a sonic or visual foundation that was transcoded from proteomic and/or genomic information – i.e. protein or DNA/genetic sequence data is converted to sonic/visual sequence through custom-built software. I spent a number of years composing media (sonic and video) as works or sound objects from the genomes and/or expressed proteins of extinct or endangered species – specifically, species that were lost to the human hand in the 19th and 20th centuries, and conceivably species that our great grandparents could have seen daily and now we will never witness. This process gives me both a scientific transcoding platform to think and listen through as I further explore immersive content that I need to witness and acquire.

In light of our current environmental circumstances we have been presented with critical prospects for listening. It is implicit that the realizations of climate change will greatly impact acoustic ecologies – the core of acoustic variability is carried by the basic factors of temperature and humidity. On the bioacoustic side the induction of birdsong and auditory pathways is driven by environmental factors. As immediacy – in January 2017 reports of climate warming causing major shifts in the way sound moves in the Arctic Ocean and the Beaufort Sea came in from the scientists at Woods Hole.

A channel in the ocean called the Beaufort Lens will undoubtedly change the acoustic ecologies and communication dependencies for species in this Arctic biome. Our consciousness of the fragility of acoustic ecologies needs even more attention – this erosion is yet one more cascade happening before us, and one that we should now be listening attentively for.

In continuing this creative line of inquiry, in 2016, I became engaged through the National Academies (of Science, Engineering and Medicine) Keck Futures Initiative (NAKFI) in a collaborative research project with the visionary composer Dr. Jonathan Berger of Stanford’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA). NAKFI is an initiative aimed at breaking open high-risk and novel ways of collaborating and knowing in the sciences. 2015-16 was the first time NAKFI converged scientists and artists together in their think tank style collectives. Our hybrid investigation, Project ECAT (EcoAcoustic Toolkit), is a collaborative art-science investigation to advance the creative and scientific literacy of ecoacoustics.

To broaden ecoacoustic literacy we are developing new openly accessible digital sound recording hardware and software that can result in the three-dimensional resolution of ecological soundscapes. For example, we are developing methods for the recording of three-dimensional sounds in a number of Western Hemisphere at-risk ecologies where we can characterize the acoustics of a canopy forest space to understand the auralization or the way that sound travels, reflects and resonates in the natural ecological space. Through these methods we can model and archive three-dimensional acoustic environments for later reference for ecological protection and preservation. These tools will be made available to artists, scientists and citizen scientists.

To date, this project has been fieldwork intensive and has taken our recording sessions to far ranging remote field sites in the Western Hemisphere to spatially characterize the endangered and at-risk ecological soundscapes of the Amazon rainforest, the Peruvian cloud forests, the Cordillera Blanca of the Andes, the California redwoods and the ancient primary forests of Vancouver Island in British Columbia, Canada.

In parallel to my time in the outback, Jonathan has done intensive development and creative work to advanced methods of 3D Ambisonic recording and auralization of archaeoacoustic and architectural spaces in Rome. He has produced multiple installation and new compositional works focusing on the notions of climate change and extinctions in the historical times of the Roman Empire. Project ECAT’s base methods for spatial sound characterization have been adapted from work conducted in the field of archaeoacoustics and primarily informed from a project base investigated at Stanford’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) by Dr. Miriam Kolar and Dr. Jonathan Abel.

In this our final year of this project we are building advanced 3D recording methods, solidifying our archive of auralization and ecoacoustics data and prototyping the ecoacoustic software and hardware toolkits we will be introducing. We are especially excited that we are now applying the results of our tool development and field sampling to new experimental sounds compositions, multimedia performance and interactive installations to creatively convey the fragile nature of ecological soundscapes to public audiences. Our initial prototype works are utilizing voice interactivity in a call-and-response configuration that places a participant’s voice into the virtual space of an endangered ecoacoustic soundscape as they recite classic texts from various cultural insights into the sacredness of forests. Through our custom software and hardware, the audience participant calls into the virtually modeled forest and their own voice responds back to them in the spatial ecological memory of the reanimated space.

The hope is that audience engagement with such immersive experience may re-mediate the patterns of lost ecological memory as a means of facilitating a discourse into the fragility and elusiveness of life in a time of cascading extinctions.

(Top image:Â ArthropodaChordataConiferophyta, live cinema performance, Timothy Weaver, 2013-15.)

______________________________

Timothy Weaver is a new media artist, life scientist and bioenvironmental engineer whose concerted objective is to contribute to the restoration of ecological memory through a process of speculative inquiry along the art | science interface. His recent interactive installation, live cinema, video and sonic projects have been featured at FILE Hipersonica (Brazil), Transmediale (Berlin), New Forms Festival (Vancouver), Subtle Technologies (Toronto), Korean Experimental Art Festival, Museum of Modern Art (Cuenca, Ecuador), the Seattle Center, the Denver Art Museum, Boston CyberArts, SIGGRAPH, the New York Digital Salon & the National Institutes of Health (Washington, DC). Timothy is Professor of Emergent Digital Practices specializing in biomedia, sustainable design and emerging forms of interactive expression at the University of Denver, Denver Colorado.

Artists and Climate Change is a blog that tracks artistic responses from all disciplines to the problem of climate change. It is both a study about what is being done, and a resource for anyone interested in the subject. Art has the power to reframe the conversation about our environmental crisis so it is inclusive, constructive, and conducive to action. Art can, and should, shape our values and behavior so we are better equipped to face the formidable challenge in front of us.