This post comes from the Artists and Climate Change Blog

Last year, I traveled to the Galápagos Islands. I felt I had stepped back to a place I recognized from my past but had only experienced in my imagination. As a child, when the world seemed so big and boundless, I explored landscapes like this, untouched by humans. But as I stood upon the volcanic rock of this dynamic ecosystem filled with life, I felt the fleetingness of its being in every step I took. Both beautiful and foreboding, I wanted to somehow envelop it, to enclose this place in a cavity of myself where I could keep it, protect it, defend it, and sustain it.

But, who am I? I’m not a scientist who can uncover data-based solutions. I am not a politician who can develop a multi-national logistical plan for action. I am an artist, and artists possess a unique and crucial skill – the ability to communicate. Scientists and politicians have their own particular vernacular, but artists have the ability to access that part of human interconnectivity that cannot be communicated through language. My artistic practice is a social practice – my task is to create methods and approaches that destabilize linear ways of knowing and understanding the world.

In December 2015, I created A Poem for Lonesome George dedicated to the last Pinta Island tortoise who passed away in 2012, 40-years the sole survivor of his species. The work was designed for the Boston Convention Center’s marquee – an 80ft x 24ft seven-screen outdoor video display. Inspired by the work of Krzysztof Wodiczko, I used the architectural structure of the building to create a memorial for George – its physical size a testament to the significance of George’s existence and his passing. I created the piece not only for George, but for us as well, because in 2012 on that research station in the Galápagos, a part of us died too. A part of our planet, a part of our humanity, and a part of our existence was gone. The work had its intended effect: people wanted to know more about George, and they expressed cross-species empathy for a dead reptile. That is the power and the possibility of art.

My recent project, Wish You Were Here: Greetings from the Galápagos, is a three-channel experiential video installation. As an interdisciplinary artist, I utilized an assortment of mediums and strategies: digital animation, photography, collage, traditional drawing, and live action video. The viewer stands in the center of the piece, with imagery in front of them and on either side. The left and right screens represent the change of the seasons and atmospheric phenomena – the original habitat of now extinct species. Extinct animals begin to emerge on these screens; they appear chronologically as they disappeared from earth. The middle screen is filled with still present animals, a composite of travel photographs I took in Galápagos. Slowly, they transition into extinct species by changing from color imagery to pencil sketches, then disappearing from the middle screen and appearing on the left or right. A human figure (me) moves within the landscape as both a guardian of collective memory and as an embodiment of present-day eco-consumerism.

The installation navigates the unsteady terrain between environmental advocacy and tourism, conservation and consumption, sustainability and exploitation. There is a tension between the exploitation of the natural world, and the desire to preserve and sustain it. I appear as the artist, studying and sketching these extinct animals – acting as an archivist or a dreamcatcher – attempting to write them into our collective memory. I also participate in conventional tourist-based activities: taking and posing for photos, relaxing, reading, doing bad yoga. I appreciate the animals, but am completely oblivious to their transformation and eventual relocation to the realm of mythology. Through all my actions, I invite the viewer to recognize themselves.

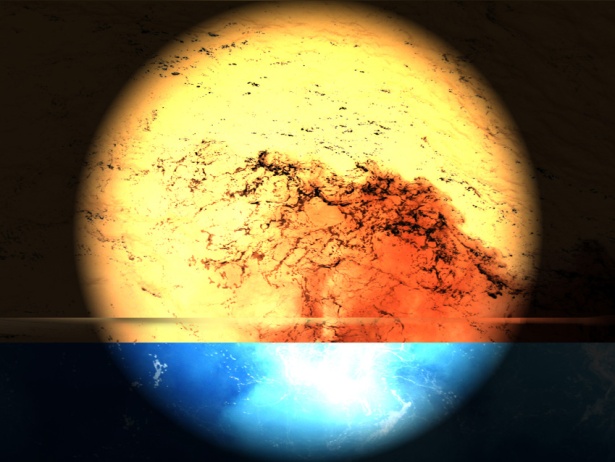

In my work, I often create fantastical landscapes that are intended to provide a physical representation of a mental space. This surrealist approach to communication exposes the limitations of language, and opens up a space for the viewer to explore alternate ways of accessing and connecting to the emotional realities of others. In this piece, I make reference to the earth as a conscious being that experiences climate change as trauma – impact in one sphere creates profound effect in another. I utilize abstracted brain scan imagery, animated synaptic flashes, and the interactive compartmentalization occurring on all three screens to convey the interconnectivity of human action/impact, as well as how our existence is directly linked to the existence of other species. I’m also interested in the tension between our ability to employ medical devices to “read†physical changes in the brain based on trauma response, and the blatant inadequacy of language to convey the actual experience of trauma. The piece concludes when an ominous sun – visually akin to popular atomic bomb footage – devours the entire landscape and the viewer is left alone in a pure white light. The explosion of the visuals is in stark contrast to the sound of absolute silence; there is no life remaining to hear the destruction of our world.

Ultimately, it is the interconnectivity of our existences that will save or destroy us. Wish You Were Here: Greetings from the Galápagos is intended to construct a quiet space for reflection on oneself and on one’s manner of engagement with the world. The meditative quality of the piece will kindle action by allowing time for reflection on our intimate kinship with other species. In today’s world, the space for this sort of contemplation is not readily available or even encouraged, but it is necessary if people are to make significant changes in their lives. My work creates an alternative space, a unique experience, in order to initiate a new dialogue about environmentalism. By providing the opportunity for a private moment, Wish You Were Here encourages radical thinking about the impact of our daily practices and the urgency of the challenges facing our planet.

(Top image: Wish You Were Here: Greetings from the Galápagos (detail image) by Allison Maria Rodriguez, 3-Channel Video Installation, 2017.)

______________________________

Allison Maria Rodriguez is a Boston-based interdisciplinary artist working predominately in new media, film/video and installation. With themes ranging from human migration to data visualization, her work converges on a desire to understand the space within which language fails and lived experience remains unarticulated. Rodriguez’s work has been exhibited internationally in both traditional and non-traditional art spaces. Her most recent projects include several large-scale public art video installations commissioned by Boston Cyberarts and the Massachusetts Convention Center Authority. She received her MFA from Tufts University/The School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

About Artists and Climate Change:

Artists and Climate Change is a blog that tracks artistic responses from all disciplines to the problem of climate change. It is both a study about what is being done, and a resource for anyone interested in the subject. Art has the power to reframe the conversation about our environmental crisis so it is inclusive, constructive, and conducive to action. Art can, and should, shape our values and behavior so we are better equipped to face the formidable challenge in front of us.

Warmer, open to a piece by

Warmer, open to a piece by