This post comes from the Artists and Climate Change Blog

“Why I’m Breaking Up with Aristotle†by Chantal Bilodeau was originally published on HowlRound, a knowledge commons by and for the theatre community, in April 2016.

It’s me, of course, not him. After all, Aristotle and his posse of ancient Greeks gave us many of the elements that have become the foundation of Western Civilization. They gave us human rights, democracy, and the Olympics. They gave us philosophy, significant advances in mathematics, and medicine. And they gave us dramatic structure, the golden principle behind all of Western dramatic literature.

That’s a lot to admire, I know. But I’m still breaking up with him.

The thing is, our relationship has run its course. Given the new challenges brought on by a rapidly changing world and our inability to communicate effectively around them, and given the fact that I feel he doesn’t really see me as a woman, it’s best we go our separate ways. I have no doubt he’ll continue to be influential in my life—we had many good years together and I will forever value the lessons I learned from him—but in the end he’s too controlling and I need to break free.

To be completely honest, I’ve been feeling a growing discomfort for quite some time. It wasn’t exactly boredom and we were not fighting either but we didn’t seem to fit anymore. Round hole, square peg, type of thing. And then not too long ago, I came across Josephine Green’s presentation “The Power of Abundance.†Boom. Suddenly it all became clear.

The idea is this: Though Aristotle and his pals gave us all the good things mentioned above, they also subtly imparted their worldview and its attending values to us. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. That worldview has allowed human civilization to thrive for over twenty-five hundred years. But in the context of a world that is now massively different from ancient Greece—more populated and exponentially more connected—that worldview has become a liability rather than an asset.

On the most basic level, ancient Greeks were ruled by a bunch of unpredictable gods whose whims directly affected every aspect of human affairs. Largely ignorant of the natural forces shaping life on earth, people assigned power and knowledge to these supernatural beings and lived under their capricious rule. Then, as empirical knowledge developed through the study of science, some of the powers previously assigned to gods became better understood and a single Almighty God replaced the jolly bunch. The Almighty God prevailed until the industrial revolution when our increased resources and self-reliance moved us away from the divine and into the arms of mega-corporations.

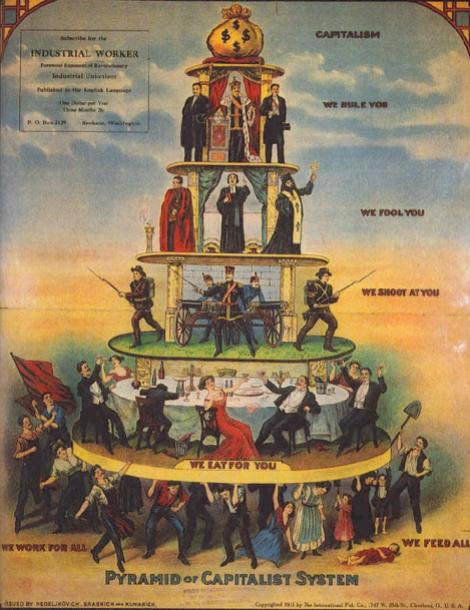

Though these represent big shifts in how we conceive the world and our place in it, the underlying assumption—that power is at the top and everybody below is subservient—has remained unchanged. In fact, it is so deeply embedded in our culture that most of the time we don’t notice it.

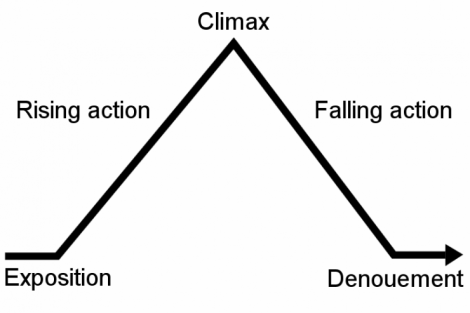

The simplest way to illustrate this concept is with a pyramid. Power and wealth live at the top, in the hands of a minority, while the majority exists at the bottom to support the top. This is how religions are organized, how monarchies thrived, and how today’s capitalist system functions. But as Green points out in her presentation, the pyramid model is not an absolute truth. It’s a worldview. Or put another way, it’s a function of the stories we tell ourselves about who we are. It should come as no surprise then that the structure we use to build our societies, and the structure we use to shape our stories, are one and the same. Aristotle’s theory of dramatic writing, later modified by German playwright and novelist Gustav Freytag, is a pyramid. Rising action on one side, climax at the top, and falling action on the other side.

This form of storytelling flourished at a time where man needed to conquer in order to survive. Life was hard; nature, a hostile force to be reckoned with; and other nations a constant threat. Subjugating nature was a matter of life or death, while subjugating the masses was a way to secure power and resources, and build a sense of security. As this worldview and the stories used to keep it alive were passed down generations, they were (and still are) used to justify a slew of abusive behaviors such as feudalism, colonialism, slavery, genocide, violence against women and children, economic injustices, the plundering of natural resources, etc. In addition, Aristotle excluded a very important point-of-view from his theory. The festival of Dionysus, where ancient Greek theatre began, was for men only. Aristotle’s “core data†was in fact stories written by men, for men, and about men.

How can a dramatic theory developed in these conditions represent the world we live in today and the world we are striving to create? We’re living through an unprecedented transition in human history where we’re slowly shifting from a hierarchical worldview to a heterarchical worldview. New technologies and social digital media have created a complex world and in the process, flattened the pyramid into what Green calls a pancake, with relationships organized laterally instead of vertically. Given this new paradigm, is it ethical to embrace a dramatic form that was designed to justify inequality and violence? Can we, writers, say something new, something of value, if we don’t break free from that mold? If we don’t find a way to write ourselves out of the pyramid?

My friend Koffi Kwahulé knows this problem intimately. An African playwright born and raised in Côte d’Ivoire, Koffi spoke his tribal language at home and was taught French—a legacy of French colonization—in school. He was also taught playwriting according to the classical French tradition. But like most of his contemporaries, he realized that the experience of colonialism can’t be expressed using the language and forms of the colonizer. Koffi had to find a way to appropriate the French language and make it sing a different song. He had to develop a dramatic form that would express his own unique experience. Over the next thirty years he developed a unique aesthetic, akin to jazz music where, in the words of NYU Professor Judith Miller, “Kwahulé intends his theatre—with its stylistic nods to jazz, through its riffs, refrains, and repetitions, through references to composers and musical numbers—to capture both something of the pain of contemporary existential despair and the exuberant energy of improvisation.†Borrowing from a form developed by African American slaves struggling to maintain their cultural identity, Koffi reconceives jazz music to express the pain of French colonialism and by extension, the pain of oppression.

The idea is not new. Many playwrights—including Beckett, Churchill, Pinter, and Kushner, just to name a few—have played with form. But they did so in isolation and it could be argued that their concern was mainly aesthetic. In contrast, what we need today is a conscious use of dramatic structure in service of societal change. The hierarchical pyramidal worldview is based on values that promote competition, control, and a sense of scarcity—there isn’t enough to go around. And since we have to fight for everything, there will always be winners and losers. The heterarchical worldview, on the other hand, promotes innovation, collaboration, and creativity. It works with the assumption of abundance—there is enough. We just need to learn to look for it and distribute it more equitably.

Moreover writing plays where scenes have a neat cause and effect relationship in the Internet age where ideas emerge through associations, and where biomimicry is replacing old mechanical principles, seems archaic. And with quantum physics telling us that two realities can exist at the same time and that an observed behavior is forever changed by the act of observation, shouldn’t we explore all the possible realms of existence and consciousness rather than stick to a thin sliver of observable reality? Humans are not the center of the universe anymore. Time is no longer linear. Our species could go extinct. These are profound ideas that should inform how we structure our stories.

I’ve seen some exciting plays recently that grapple with these concepts. And these plays have both nothing to do with climate change and everything to do with climate change. None of them addresses the topic directly. But embedded in their structure is an attempt to break down the many pyramids that rob us of power and agency, and to view humanity as part of a vast web of life. O, Earth by Casey Llewellyn, Smokefall by Noah Haidle, and CollaborationTown’s Family Play (1979 to Present) all possess a new sensibility that positions us within a larger and more compassionate frame. These playwrights are seizing the moment, they’re sensing what’s floating in the ether and responding to it. They’re creating the sustainable culture of tomorrow.

So this is it. For better or for worse, I’m breaking up with Aristotle. I don’t harbor any bad feelings towards him; I did love him. For a long time, our relationship was fun, passionate, and intellectually stimulating. But then things changed.

Maybe I grew up and he didn’t. Or maybe it was always meant to end this way, with us going down our separate paths. It’s the end of an era, that’s for sure. But it’s also the dawn of a new age. Though it’s not easy to leave the comfort of the known and knowable, I’m excited at the possibilities that lay ahead, at the chance to craft stories that are in line with my values and my vision of what the world is and can be. I’m excited to do my part and to bring all of me in that effort. I think I’ve earned the right to.

So long, Aristotle. It was swell.

Artists and Climate Change is a blog that tracks artistic responses from all disciplines to the problem of climate change. It is both a study about what is being done, and a resource for anyone interested in the subject. Art has the power to reframe the conversation about our environmental crisis so it is inclusive, constructive, and conducive to action. Art can, and should, shape our values and behavior so we are better equipped to face the formidable challenge in front of us.

Go to the Artists and Climate Change Blog

Powered by WPeMatico

Poster for Theater in Asylum’sÂ

Poster for Theater in Asylum’s  Rehearsal for Theater in Asylum’sÂ

Rehearsal for Theater in Asylum’s