This post comes from the Artists and Climate Change Blog

By Guest Blogger Christina Catanese

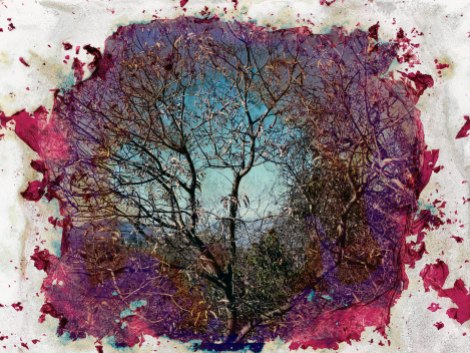

Featured Image:Â River print (detail) by Kaitlin Pomerantz & John Heron.

In Going Up: Climate Change + Philadelphia, eight artists from around the country – Daniel Crawford, Lorrie Fredette, Jim Frazer, Eve Mosher, Jill Pelto, Kaitlin Pomerantz and John Heron, and Michelle Wilson – explore the future of a hotter, wetter Philadelphia.

Several of the artists use data as a point of departure, and others suggest imaginative ways of thinking about problems and solutions, even considering the responsibility of art to reduce its own carbon footprint. The gallery contains artwork made for indoor display as well as pieces that document social practice or conceptual art that happened outside the gallery or studio, less focused on the product than the process. Many help us to notice our surroundings more closely, observing the small and incremental changes around us that track global change.

Going Up opened on September 24th at the Schuylkill Center, and runs through December 2016.

Artist duo Kaitlin Pomerantz & John Heron explored waste and water pollution, presenting an imaginative way to think about the problem and potential solutions. They created handmade paper works they call river prints during a residency at Recycled Artists in Residence, a program which gives artists access to the waste stream at a Northeast Philadelphia recycling facility. The fourteen-foot-long piece in our gallery was made from discarded paper and denim, and then dipped into a polluted estuary in the Delaware watershed, drawing up oils and residues from the water surface to “print†on the surface of the paper. Pomerantz writes, “Though I wouldn’t venture to say that our river prints did anything real in the way of remediation, for me, they began to suggest new ways of thinking about how to act on the messes we’ve made of our planet’s water…Our river prints project got me thinking about the value in making people actually see pollution, as a way to spur more conversations about new ideas in remediation.â€Â These artists also raise the question of the responsibility of art to reduce its own carbon footprint – their work is created entirely from found materials with no new art products needed.

Other artists in Going Up are interpreting dimensions of climate change related to health, biodiversity, water, waste, and food – encompassing of a broad range of kinds of climate change impacts.

Daniel Crawford created a string quartet composition from climate change data that uses music to highlight the places where climate is changing most rapidly. In Planetary Bands, Warming World, each note represents the average temperature of a single year of four regions of the globe, demonstrating change over time and inspiring listeners to use different senses to understand these warmer years.

Lorrie Fredette presents a ceramic installation responding to Lyme disease, which is projected to spread as climate change increases the range of suitable tick habitat. Made up of 685 individual ceramic pieces referencing the form of the Lyme disease bacteria, the shape of the installation responds to the shape of the Schuylkill Center’s zip code, one of the highest incidences of Lyme in Philadelphia.

Jim Frazer’s paper works are derived from bark beetle chewing patterns, an issue for forests which is expected to increase with a warming climate.

Jill Pelto uses climate change data as a point of departure for her watercolor works to communicate scientific research visually. In addition to three works exploring global trends, Pelto created a new work for Going Up interpreting four sea level rise scenarios for Philadelphia.

Eve Mosher’s High Water Line (in Philadelphia and other cities) engaged communities with local issues of sea level rise and flooding. In 2014, Eve Mosher used surveyor’s chalk to mark ten feet of storm surge, the level to which water would rise in particular Philadelphia neighborhoods under certain climate forecasts.

Michelle Wilson’s Carbon Corpus project explores the implications of individual food choices for global climate change. A conceptual project, she shows a video documenting the project along with an 8.5 foot cube, which occupies the space that 35 kilograms of CO2 takes up in the atmosphere, the amount saved by eating a vegan diet for one week.

Dichotomies of scale pervade the gallery space. The colors and forms of the works, though, have a quietness and subtlety to them. In this way they are analogous to climate change itself: massive in scale but local in effect; happening gradually yet creeping up on us; a dominant presence, yet allowing us to move through and around it without making much of a change to the path we are on, at least for the present.

The show’s title references this trajectory along with scientific trends which often point in a terrifying upward direction. Yet, in invoking rising movement, we also pull hope into the climate change conversation. Climate change doesn’t only present challenges and doom-and-gloom scenarios, but also opportunities for innovative solutions, cooperation on an unprecedented scale, perhaps even a more sustainable and equitable society. These eight artists turn our focus both inward, toward the impacts in our own lives and communities, and upward, toward what we can do about them.

Eve Mosher and assistants draw the High Water Line in Northeast Philadelphia.

In 2014, Zadie Smith wrote on climate change that, “In the end, the only thing that could create the necessary traction in our minds was the intimate loss of the things we loved.†Art can be an anchor for this traction. Though art about climate change often contains elements of loss, the end result somehow feels more optimistic. Smith continues, “I found my mind finally beginning to turn from the elegiac what have we done to the practical what can we do.†Artists today have the unique potential to help more minds make this same, critical turn.

Together, the artists in Going Up have created a new avenue into the tangled knot of climate change. Instead of bombarding us with data, the information is transformed into beauty, into innovative communications and evocative images that stand in their own right as works of art, but which also invite the visitor to understand our warming world in new, personal ways.

Going Up is supported in part by a grant from CUSP – the Climate & Urban Systems Partnership, a group of informal science educators, climate scientists, learning scientists and community partners in four Northeast U.S. cities, funded by the National Science Foundation to explore innovative ways to educate city residents about climate change.

______________________________

Christina Catanese is the Director of Environmental Art at the Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education. Founded in 1965, the Schuylkill Center is one of the first urban environmental education centers in the country, with 340 acres of fields, forests, ponds, and streams in northwest Philadelphia. We work through four core program areas: environmental education, environmental art, land stewardship, and wildlife rehabilitation. The environmental art program incites curiosity and sparks awareness of the natural environment through presentations of outdoor and indoor art.

______________________________

———-

Artists and Climate Change is a blog that tracks artistic responses from all disciplines to the problem of climate change. It is both a study about what is being done, and a resource for anyone interested in the subject. Art has the power to reframe the conversation about our environmental crisis so it is inclusive, constructive, and conducive to action. Art can, and should, shape our values and behavior so we are better equipped to face the formidable challenge in front of us.

Go to the Artists and Climate Change Blog

Powered by WPeMatico

![Terre Neuve Beach in Camargue [43°28'1.98"N; 4°11'17.83"E]-2016](https://artistsandclimatechange.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/combined-pics.jpg?w=470&h=113&resize=470%2C113)

![Aresquiers Beach [43°29'52.41"N/ 3°52'8.52"E]- 2015.](https://artistsandclimatechange.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/picture4.png?w=470&h=143&resize=470%2C143)

The following set of links provides a few examples of the myriad strategies currently available to architects, designers, engineers and urban planners to reduce emissions, conserve energy, build resilience, and prepare for inevitable sea-level rise in coastal urban centres:

The following set of links provides a few examples of the myriad strategies currently available to architects, designers, engineers and urban planners to reduce emissions, conserve energy, build resilience, and prepare for inevitable sea-level rise in coastal urban centres: