This post comes to you from EcoArtScotland

Kate Foster and Claire Pençak have written this article to highlight the ways that they as artists (visual and dance/choreographic), have been engaged with land use and in particular the development of Land Use Strategy for Scotland through the Borders Region Pilot. The article specifically responds to a previous piece on ecoartscotland which asks “What can the arts contribute to a Land Use Strategy for Scotland?â€

Some of the really central challenges for artists working with land use issues are highlighted by Kate Foster and Claire Pençak including the discipline and practice specific languages used by environmental scientists and land managers as well as the dominance of Geographical Information Systems technologies. Kate Foster and Claire Pençak’s projects demonstrate some of the best approaches that can be learnt from the past 60 years of ecoart and the longer history of art.

Introduction

Previous posts on this topic have pointed out that government policy has made an ecosystems service approach central. This opens up questions of what to place value on, and if, and when, it is helpful to monetise an ecosystem service. Too often human interests only are considered, leading to ongoing over-exploitation of ‘natural capital’. There has also been concern that intangible cultural elements cannot be recognised by an approach dominated by Geographical Information Systems, and mapping only what exists on the ground.

This article provides an outline of how we (choreographer Claire Pençak and environmental artist Kate Foster, who both live in the Scottish Borders), have worked in parallel to the regional Land Use Strategy pilot that was conducted in Borders Region.

Creative practices can contribute ways of relating to place, and offer alternative meanings and insights that escape conventional appraisal. Artists can act as connectors between disparate approaches, and re-enchant what is overlooked. The work we describe below is marked by a commitment to improvisation and responding to context. Our consistent theme is finding ways for rural-based arts practice to engage with contemporary concerns, regional and international.

Some background to the Land Use Strategy

In way of background information, the government Land Use Strategy initiative stems from the 2009 Climate Change Act (Scotland). The Scottish Borders along with Aberdeenshire was selected to develop a Pilot Regional Strategy, which would ultimately inform the revision of the national Land Use Strategy, to be published later this year. In our region, the process was led by Scottish Borders Council in partnership with Tweed Forum who co-ordinated the stakeholder engagement programme. Tweed Forum is a membership organisation whose collective purpose is to enhance and restore the rich natural, built, and cultural heritage of the River Tweed and its tributaries.

The Land Use Strategy regional framework in the Scottish Borders was developed through mapping and a series of public consultations to seek the views of communities. This came to our attention as it coincided with Working the Tweed, a Creative Scotland Year of Natural Scotland 2013 project which was an artist led partnership project between Tabula Rasa Collaborations, Tweed Forum and Southern Uplands Partnership.

From our vantage point, it was obvious that the LUS pilot strategy was beckoning to artists to contribute to it, but it was a question of how?

The following sections describe different art projects that were considerations of aspects of land use, emerging during the period between the Climate Change Act (Scotland, 2009) and the conclusion of the draft consultation for the Land Use Strategy 2016-2021, in January 2016. We were aware of the pilot regional strategy taking place in our area, and engaged with it by attending public meetings and filling in questionnaires. This activity fed into our work; we were inspired by the ambition of sustainable land use and searched for a way that we could contribute to the debate in a way that was meaningful for us – both as artists and as local residents.

A catchment map as a talking point

Seeking to engage with the Land Use Strategy, we found the vocabulary and frames of reference were clearly suitable for conversing with land managers and land owners who were knowledgeable and skilled at the interface with government and agriculture. We could sense that the kind of language used could be impenetrable, and wouldn’t empower the broader community to connect with the ideas, which is what Tweed Forum were keen to do. Having been to a few of the public consultations, we found it tricky to know how to engage with what seemed a very prescribed, compartmentalised and ‘male’ approach.

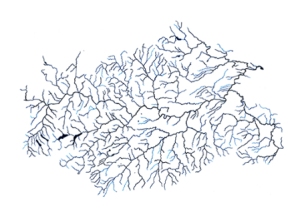

The Land Use Strategy pilot project used catchments to identify localities – an idea we had also used as a motif map for Working the Tweed (a project that is described in more detail below). Because a catchment map was not cheaply available in the public domain, we made a hand-drawn version. We found it an evocative image to engage with people. Looking at this catchment drawing moves you from the predominant perception of the Scottish Borders as a series of discrete small towns, towards seeing it as a region connected by the dense network of tributaries to the Tweed. This was an effective means for us to generate conversation and elicit local knowledge and viewpoints, for example by taking stalls in annual agricultural shows.

River Ways © Working the Tweed 2013

A Riverside Meeting concerning Resources and Land Use

Working the Tweed was an artist-led Year of Natural Scotland 2013 project that was planned prior to the Land Use Strategy pilot project. It was a nine-month programme that focussed on the diverse ways that people were working with the Tweed waters. It included a series of six riverside meeting with different themes. These meetings brought together professional creative practitioners living and working in the Tweed Catchment with scientists and environmentalists, to stimulate discussion, exchange and creative responses. They took place at different locations in the Tweed Catchment, and each meeting explored a different theme related to the Tweed Catchment Management Plan.

A first step in making the ideas behind the Land Use Strategy more accessible was to use the final Riverside Meeting to focus on two policy strategies being developed in parallel in the Scottish Borders: for culture as well as land use. The final Riverside Meeting – Mapping the Future Scottish Borders – took place at The Lees fishing shiel on the Tweed at Coldstream and explored the themes of Water Resources and Land Use. Derek Robeson, Senior Project Officer at Tweed Forum, introduced the Land Use Strategy in relation to the Tweed Rivers through the frames of Environment, Culture and Economy. It was an opportunity to look at the maps that had been created through the lens of the Land Use Strategy (e.g. Biodiversity Networks and Resilience, Sporting and Recreation, Agricultural Crops) and to consider land use in the field through a riverside walk. The meeting placed the Land Use Strategy alongside the parallel development of a Cultural Strategy for the Scottish Borders which was introduced by Mary Morrison, Director of the Creative Arts Business Network. This brought a focus on cultural landscapes to the session. The final contributor David Welsh introduced an historical perspective, with his detailed knowledge of how the line of the Border has shifted around each field and burn in its path. In the year of the Independence Referendum this had an added potency. The session as a whole provided a challenge to how artists can work with complex histories and geographies, and engage with uncertain futures. It is fully reported on this link.

At this Riverside Meeting, the point was made that the lifetime of deciduous trees defied the short time frames for which policy is made, typically a five-year period. The mature trees along the River Tweed are evidence of much older strategies of land management.

Salmon scale – a link to different places and timescales

The catchment map acted as a motif for the Working the Tweed project, and provided an overview of our region. This was complemented by looking at something close-up, a scale from the skin of a Salmon (which is smaller than a finger nail). Looking at magnified scales from migratory fish offered us another lens to perceive different rhythms of time and place that might influence daily life and work in our region.

Like a tree ring, a Trout or Salmon embodies a pattern of its growth into its scales. The Tweed Foundation collects scales from anglers, and accumulates data that helps interpret seasonal changes in the fishing catch. With a microscope an expert eye might see – for example – that a Salmon lived for two winters in the river, with a further winter at sea before returning to the Tweed to spawn.

These scales inspire a step backwards, to consider the larger picture. These fish deserve the name ‘Atlantic Salmon’ because they belong to a species who use ocean currents to drift to cold subarctic waters. Rich feeding to the west of Greenland allows them to mature before returning to their home river in mating mood.

There is room for speculation about future patterns that will be read in Salmon scales. Within ten years perhaps, the North Pole will become a navigable ocean, allowing seasonal passage to the Pacific. What impact will warming oceans have on their migration patterns and the patterns of their scales?

Thus a drawing of a Salmon scale became a second project motif, conveying connectedness to oceans, and hence the world. This led to the reflection that the Land Use pilot strategy was only considering land use within the administrative remit area. From such a narrow frame, events in wider geographical scales become ‘irrelevant’. Conversely, impacts on areas beyond the boundaries as a result of local land use can remain unconsidered.

This is a paradox for legislation stemming from a Climate Change Act, dealing with an international problem that is hard to fix in time or place, and where the actions of people in one place are acknowledged to have distant effects. To quote from an article by the academic Timothy Clark:

Climate change disrupts the scale at which one must think, skews categories of internal and external and resists inherited closed economies of accounting or explanation. (2012, page 7)

Artists can contribute reminders of the unruliness of more-than-human timescales, explore the possible meanings and experience of climate change, and question the deranged scales in common currency.

We would argue that Salmon are integral to the identity of the Tweed Catchment, and its welfare cannot be seen as separate to the wellbeing of humans.

Scaling the Tweed © Kate Foster, 2013

Approaching Choreography: A Proposal for Engagement

Following Working the Tweed, Claire Pençak began a research project funded through a Creative Scotland Artist Bursary by considering what a choreographic approach to thinking about Land Use might yield.

Approaching Choreography was an attempt to articulate an environmentally sensitive approach to dance-making and choreography through the frames of Placing and Perspective; Pathways Through; Meetings and Points of Contact and Working with Materials and Sites. It reflects on our positioning and shifts the emphasis from taking centre ‘stage’ towards margins and sidelines. This alternative framework emerged out of a series of riverside improvisations and conversations with dancers Merav Israel and Tim Rubidge, environmental artist Kate Foster and writer/researcher Dr. Wallace Heim. These took place on the Ettrick and Yarrow Waters in the Scottish Borders, and the East and West Allen Rivers in Northumberland.

Claire writes:

Choreography is concerned with space and I started by exchanging the idea of ‘space’ for that of ‘habitat’, and thought of the dancer as both creating and revealing habitat. Through this lens, habitat could be understood as ‘action spaces’ and land use became something that could be considered as performative, emerging and improvisational.

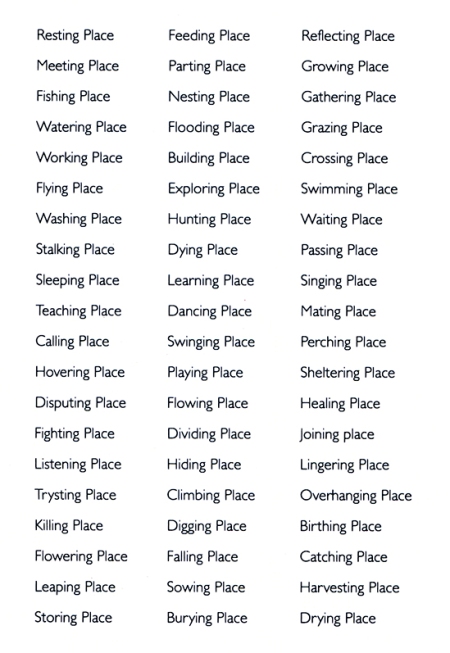

From this I developed a score as a way to proceed, a way to assist imaginative engagement, a way into playful encounters with land.

Further information is available here.

The score offers sixty examples of ways that habitat could be interpreted and worked by the diversity of species that use it – birds, fish, insects, mammals, plants and trees. It is easily understood, does not rely on land management knowledge and acknowledges multi-species. It suggests potential zones of action – on the ground, under the ground and over ground; on the water, underwater and in the air. The score can be cut up, shared, read out and passed on. Further information is available here.

River Ways © Working the Tweed 2013

This thinking was made into a small illustrated A6 booklet (Approaching Choreography: A Proposal for Engagement) as part of a collaborative project, Speculative Ground which was conducted with Jen Clarke and Rachel Harkness of Aberdeen University.

Stone LivesÂ

Stone Lives was commissioned by Aberdeen University as a contribution to the Speculative Ground project which also included an exhibition curated by Jennifer Clark and Rachel Harkness at the Anthropological Association Decennial Conference in Edinburgh, in June 2014.

Stone Lives developed from an investigation of riverbank ecology at the meeting point of the Ettrick and Yarrow, at Philliphaugh near Selkirk. Our arrival at the riverbank in an afternoon in late May coincided with a hatch of Stone Flies – aquatic insects emerging from the water to find a stone to air themselves, and shed their final larval form. The river was low and we could walk on the smoothed rock, ancient mudstones shaped and sifted by ice and water.

This is an extract from Kate’s writing on this piece:

This set me on a trail, I collected husks for some days after – keen to find them before river levels rose. I searched online too, learning that of all the insects that live in water, Stone Flies need the cleanest water. They are ecological indicators of healthy streams, flattened and adapted to be able to cling to stones in rapid currents. Apart from Trout who devour them, they are best known to fishermen, river ecologists and entomologists. As one source remarks: “they are rather endearing little creatures once you get to know themâ€.

The fossil record of Stone Flies stretches far back to the Permian, but their adult life is brief. A juxtaposition of Stone and Fly offers simultaneity at different timescales – a ‘so-far story’ (an idea that is further discussed in an article with Dr. Leah Gibbs and Claire Pençak  available here).

Stone Lives became an artwork inviting anthropologists at an international conference to share a sense of stone, and life supported.

Documentation of Improvisation and Stone Fly Adult Emergence © Tabula Rasa 2014

Further documentation of Stone Lives is available here.

A bioregional sensibility

We have, so far, offered examples of how visual art, interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary events, field work, and improvisational dance practices might offer further ways of thinking about land use. In combination, these directed us towards an ambition of bioregional sensibility, that has been articulated by Mitchell Thomashow:

‘Developing the observational skills to patiently observe bioregional history, the conceptual skills to juxtapose scales, the imaginative faculties to play with multiple landscapes, and the compassion to empathize with local and global neighbours – these qualities are the foundation of a bioregional sensibility…’

M. Thomashow, ‘Cosmopolitan Bioregionalism’, Bioregionalism, ed. M. V. McGinnis (London: Routledge, 1999), pp. 121-32 (pp. 130-31)

Borders Sheepscapes

An earlier project by Kate Foster, Borders Sheepscapes, was an exploration of sheep farming as a major land use in the Scottish Borders. This project is highlighted because it contributed a dimension to our thinking about Land Use Strategies, which are human-centred. The artist’s process of drawing in the field articulated some of the human resources of knowledge, skill and design underlying workaday pastoral scenery – as well as the part that sheep play in producing landscape. This project intended to shift humans from centre stage in landscape appreciation and reached towards a multispecies way of understanding how humans exist in the world.

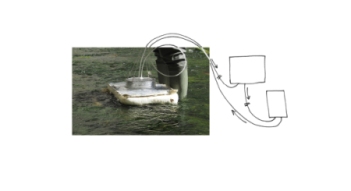

A later addition to this body of work explored the widespread use of palm oil in livestock fodder through the example of an automated milk supply for orphaned lambs.

Lac-tek, the electronic mummy © Kate Foster 2012

This work explored both the welcome benefit ‘Lac-tek’ brought to the farmers and possibly the orphaned lambs, and also the presence of palm and coconut oil in the sheeps-milk substitute (and many other animal feeds). Palm oil is an example of a highly controversial commodity, because increasing demand for this product has led to expansion of plantation monoculture in tropical countries, undermining climate change mitigation and creating further environmental injustice.

Carbon Landscapes

The Climate Change Act (Scotland) was a starting point for the Land Use Strategy. Atmospheric pollution by greenhouse gases is a complicated science, but there are straightforward ways that the movement of carbon can be inferred. These are not widely understood. Kate is piloting collaborative work that explores what artists can add to the environmental science of Carbon Landscapes.

The project Flux Chamber created a guide to carbon riverscapes with Dr. David Borthwick and Professor Susan Waldron of Glasgow University.

Image from Flux Chamber series © Kate Foster 2015

You need to have thought about what Carbon Landscapes consist of before you can start to see where carbon exchange between different reservoirs (terrestrial, marine, atmospheric) is taking place. If people are to protect naturally stored carbon, we need to develop sensibility to see how carbon is gained, lost and recycled.

For Peatland Actions, Kate worked with Nadiah Rosli on another pilot project exploring carbon landscapes, that brought together different experiences of the use and exploitation of peatlands in Scotland and South East Asia. The name of the work was derived from a government programme of  peatland restoration, and this piece was shown at the exhibition Submerge, as part of the ArtCOP 2015 programme at the Stove Network, Dumfries.

Nadiah Rosli used social media communications to convey how the toxic haze, that now frequently spreads from Indonesia to other countries in South East Asia, has come to feel normal to her family and friends in Malaysia. The haze from illegal fires makes blue sky  something to exclaim about.

River Ways © Working the Tweed 2013

Here is an extract from Kate’s description of this collaborative work:

Until recently Mosses have not been valued for their ‘ecosystem services’ but peatbogs are the most effective carbon sinks known. Conversely, peat releases greenhouse gases when it is exposed. Damaged Scottish peatlands are being restored using public money for climate mitigation – but at the same time, peat extraction is pursued privately, for example at Nutberry Moss. I see this, passing by on the A75 to Carlisle. For me (Kate), this grim landscape of carbon emission is a glimpse from the car window. Nadiah Rosli has had to breathe far more damaging airs – the thick toxic haze from fires raging in Indonesian carbon-rich peatlands. Nadiah has courageously communicated about the situation in which Indonesian rainforest is burnt to allow commodity production (including palm oil and paper pulp for western markets). Her approach insists on a focus on environmental justice, including the idea that land abuse should be understood as a crime whose victims include humans exposed to the consequences of atmospheric pollution, amongst many other species.

Nutberry Moss seen in passing, from a car © Kate Foster 2015

These are ways in which we as artists have worked to open out political attention to land use, to include more-than-human and intangible cultural viewpoints. Short-term economic gain for humans is often the main consideration within our globalised economy. However artist-led projects can explore how different kinds of land use bring both benefits and loss to different parties, by adopting an ecocentric viewpoint and juxtaposing different timeframes and geographical scales. In common with other strands of contemporary art, this work seeks to shift humans from centre stage in landscape appreciation. The anthropocentric idea that extraction of commodities is endlessly possible is challenged by eco-artwork that refuses to work within the deranged scales that are endorsed elsewhere.

Academic work informs our practices in different ways, for example there is a trend in the study of international relations that takes ecology into account. Also, the environmental humanities are producing multispecies perspectives: as Deborah Bird Rose argues, if we fail to grasp the connectivities between human and nonhuman, we cannot have insight into the ramifications of anthropogenic extinction and miss ‘our entangled responsibilities and accountabilities.’

Artists can work with these pioneering and inspiring influences to produce multi-layered understandings of place, which can also be thought of as developing a bioregional sensibility. This feeds into a process of shifting aesthetic appreciation, and being able to recognise patterns of land use – as well as land abuse – within global processes. We would also wish to take the more complex step of helping develop the relationships to place and its inhabitants, humans and others, that a contemporary land ethic requires.

Kate Foster and Claire Pençak, February 2016

ecoartscotland is a resource focused on art and ecology for artists, curators, critics, commissioners as well as scientists and policy makers. It includes ecoartscotland papers, a mix of discussions of works by artists and critical theoretical texts, and serves as a curatorial platform.

It has been established by Chris Fremantle, producer and research associate with On The Edge Research, Gray’s School of Art, The Robert Gordon University. Fremantle is a member of a number of international networks of artists, curators and others focused on art and ecology.

Powered by WPeMatico

Glasgow Centre for Population Health

Glasgow Centre for Population Health

There is much to explore in this Almanac of entries, some more sculpted than others, compiled by the poet Gerry Loose as he wandered the familiar and foreign oakwoods of Sunart and Saari in 2007, 2008 and 2010.

There is much to explore in this Almanac of entries, some more sculpted than others, compiled by the poet Gerry Loose as he wandered the familiar and foreign oakwoods of Sunart and Saari in 2007, 2008 and 2010.