This post comes to you from EcoArtScotland

SoilCulture: bringing the arts down to earth, from theCentre for Contemporary Art in the Natural World (CCANW) and Falmouth Art Gallery published in collaboration with Gaia Projects is the culmination of years of work—comprehensive documentation of a significant exhibition, nine curated artist residencies, and a Soil Culture Forum. It includes photographs and essays detailing the contributions of the artists involved, as well as personal reflections on theForum, and descriptions of events held at Plymouth University, and at Create, Bristol City Council’s environmental centre, all coordinated to coincide with the United Nations International Year of Soils in 2015.

Floodplain soil developed in sand, North Wales. Photo: Bruce Lascelles

After a brief introduction by the directors of the CCANW, we are, fittingly, introduced to soil – both in an “Homage†by Patrick Holden, and more in-depth, in “What is Soil?†by Dr. Bruce Lascelles. It’s really refreshing to pick up an art book about a given subject and begin reading about that subject from the point of view of a scientific researcher. We do not begin with say, soils’ depiction in art through the ages, or with some overly poetic meandering about the modern cultural meanings of soil (though Daro Montag gives a good overview of soil in culture in “Speaking of Soil,†detailing soils’ relationships to language). Instead, we begin with a very practical overview of what soil is, on a scientific level, after an extended essay from Holden about the importance of microbial communities, comparing the function of the soil to that of the human gut.

In beginning with these scientific facts and research on soil, the book reminds us that soil is a global entity, and something upon which we are interdependent. It acknowledges that within the UK there are several hundred varieties of soil, and opens up space for potentially complex dialogue. While there are a diverse number of approaches to making art with/and/about soil included in the book, they remain rooted in conceptual methodologies and approaches. A workshop described later in the book as replicating a Japanese technique for making soil-balls is one of the rare non-Western perspectives that the book holds. It makes sense, to a certain extent, that a UK-based exploration of soil would be culturally- and site-specific in nature, and the examination of work within the contemporary conceptual is in-depth. But the potential for an even more global, expansive dialogue is sometimes lost.

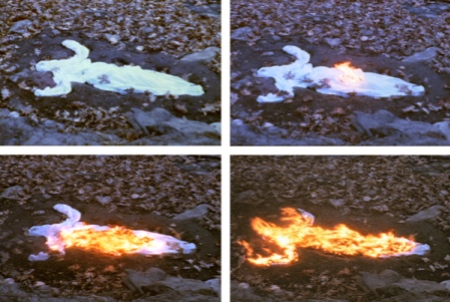

Stills from ‘Alma Silueta en Fuego (Silueto de Cenizas)’ 1975. Super-8 colour silent film transferred to DVD. Photo: The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection

From its material, scientific beginning, the book goes on to detail a major traveling exhibition, Deep Roots, featuring the works of known artists like Mel Chin, Richard Long and Ana Mendieta, as well as potentially less internationally known names, such as Paolo Barrile. Within these works, we see soil positioned as a pigment, a currency, and as a site for research.

Claire Pentecost, Soil Erg, installation in dOCUMENTA(13) in Germany 2012. Image courtesy of the artist.

It’s great to see Claire Pentecost’s work Soil Erg featured, a re-imagining of soil as a currency, complete with soil ingots and soil-paper currency notes (full disclosure: I was a student of Pentecost’s at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago). Each artist is given a two-page spread in the book, with large images and text. The work is primarily contemporary conceptual: there’s no attempt to incorporate, say, more traditional clay sculpture, or other folks forms of making art with soil. But overall, the exhibition documentation gives a good overview of soil as engaged with by a series of contemporary, established artists.

Mel Chin, Revival Field, 1991-ongoing

One point of disappointment, especially given the books’ promising relationship to science, is the treatment given to the research connected to Mel Chin’s Revival Field. This work is so singularly important to environmental art it has become a kind of sacred cow. While it’s true that Revival Field has a significant impact on research in phytoremediation, Sue Spaid has noted previously that it was concerns about perceptions of the validity of the science that prompted subsequent re-plantings.* In SoilCulture, these re-mountings are referred to simply as other versions of the project. There’s a limited amount of space given to each artist in the book, but it’s a shame that more time wasn’t taken in this volume to unpack the relationship between the scientific research and this project over time, as this is a less-often discussed but important aspect of the legacy of the work. Moments like this represent opportunities lost for a more expansive, critical discourse, especially since this art/soil/science relationship proves to be consistently important to the documented programming. If this was something that was expanded on in the live events, it isn’t made clear in the publication.

Karen Guthrie, Residency 2014, Hauser & Wirth Somerset

The book moves on to focus on nine emerging artists who were given the opportunity to embed themselves in various context to explore soil with scientists, at farms, and in a botanical garden, in a section called Young Shoots. These explorations include a distilled soil work by Karen Guthrie, a “Brest Plough o’ metric†by Paul Chaney, and an attempt to manufacture soil by Something & Son. The works bridge the scientific and the artistic in engaging and effective ways, and speak to emerging interdisciplinary practices. In these projects, soil and its culture are regarded as inspirational material in-and-of-itself, a further remove from historical art cannons, informed by science, engineering, and ecological imperatives.

Detail of ‘Breast Plough’o’metric’. Photo: Martyn Windsor

.

This bridges very well into Soil Culture: Dig it, a chapter based on an exhibition of the same name, in which the studio and the scientific laboratory are brought into the same space. Residency artist Lisa Hirmer (DodoLab) worked alongside Dr. Rob Parkinson, an Associate Professor in Soil Sciences and some colleagues from the School of Biological Sciences in Plymouth University, exploring peat and atmospheric carbon, among other collaborations, and the exhibition space displayed research tools and samples from scientific as well as creative explorations. A fitting exploration for the arc of the project.

It’s followed by Soil Culture at Create, an overview of live and educational programming at Bristol City Council’s environmental centre. A series of “Soil Saturdays†framed workshops, talks, culinary demonstrations, performances, and artistic interventions around the theme of soil, in temporary explorations. It serves well as documentation (each Saturday has a photo and a summary), but is probably best read by itself in a separate sitting, since at that point the reader has been steadily subsumed in the art/soil/science exploration, and it is a condensed format.

Thankfully, the next section is a series of short essays in response to the Soil Culture Forum, a three-day symposium converged by Research in Art, Nature & Environment (RANE) at Falmouth University. This section of the book is both satisfying and frustrating. Its personal tone and short form makes the reader feel a bit like they were in a room with a bunch of well-informed folks reminiscing, reflecting both on soil and on the event of the Forum. Valid questions are raised about culture’s relationship to soil: one of the most satisfying passages comes from Mat Osmond’s report on Richard Kerridge,

Of course, this comes after Holden’s assertion that the micro-organism is drastically important to the soil, so rather than reframe the arts as small, humble, or insignificant, this statement has the effect of positioning the arts as deeply embedded, important, in dialogue with its surroundings. I personally deeply appreciated this reframing.

Unfortunately, it is followed in other shorter essays by familiar tropes in sustainability culture, like the demand for a universal spiritual connection to the Earth, or a singular definition of love that includes the non-human (Stephen Harding’s assertion, for instance, that ‘the only way we can address these problems is through love’). These demands do much to flatten the attempts at diversity in the dialogue. It’s a common problem in the creation and discussion of environmental work that the overwhelming impetus to celebrate has the effect of universalizing, normalizing, and undermining safe spaces for questioning or critical discourse. It’s easy to make such beautiful statements—who can argue with love? But they unintentionally undermine a greater diversity of respectful relationships to soil.

SoilCulture is, ultimately, the documentation of a strong collection of artists exploring soil at a time when its importance and preciousness is politically and ecologically pressing. This puts some artworks in the position of celebrating or propagandizing. While these efforts may be needed, the conversation that SoilCulture frames also points to the importance of diversity and critical discourse in ecological/cultural work, largely because such elements are sometimes lacking in its own curation. Regardless, the projects put forth solid juxtapositions of scientific and artistic research with soil, including artist/scientist collaborations, and research processes reframed. It is a fascinating snapshot in time of artists engaging with a crucial issue.

SoilCulture is, ultimately, the documentation of a strong collection of artists exploring soil at a time when its importance and preciousness is politically and ecologically pressing. This puts some artworks in the position of celebrating or propagandizing. While these efforts may be needed, the conversation that SoilCulture frames also points to the importance of diversity and critical discourse in ecological/cultural work, largely because such elements are sometimes lacking in its own curation. Regardless, the projects put forth solid juxtapositions of scientific and artistic research with soil, including artist/scientist collaborations, and research processes reframed. It is a fascinating snapshot in time of artists engaging with a crucial issue.

* 2002. Ecovention: current art to transform ecologies, Cincinatti, Ohio: The Contemporary Art Center, p.7

Full disclosure: the author is colleagues with one of the residency artists, formerly worked for one of the Soil Culture Forum presenters, and was, as noted above, a student of Claire Pentecost, one of the professionally exhibited artists featured in the book.

All images provided by the publishers.

BIOGRAPHY

Meghan Moe Beitiks is an artist and writer working with associations and disassociations of culture/nature/structure.  She analyzes perceptions of ecology though the lenses of site, history, emotions, and her own body in order to produce work that analyzes relationships with the non-human. She was a Fulbright Student Fellow, a recipient of the Claire Rosen and Samuel Edes Foundation Prize for Emerging Artists, and a MacDowell Colony fellow. She has taught performance at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and exhibited her work at the I-Park Environmental Art Biennale, Grace Exhibition Space in Brooklyn, Defibrillator Performance Art Gallery in Chicago, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the House of Artists in Moscow, and other locations in California, Chicago, Australia and the UK. She received her BA in Theater Arts from the University of California, Santa Cruz and her MFA in Performance Art from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. www.meghanmoebeitiks.com

ecoartscotland is a resource focused on art and ecology for artists, curators, critics, commissioners as well as scientists and policy makers. It includes ecoartscotland papers, a mix of discussions of works by artists and critical theoretical texts, and serves as a curatorial platform.

It has been established by Chris Fremantle, producer and research associate with On The Edge Research, Gray’s School of Art, The Robert Gordon University. Fremantle is a member of a number of international networks of artists, curators and others focused on art and ecology.

Powered by WPeMatico